Twenty-five years ago, Vigen Guroian, Ph.D., a theologian and professor of religious studies, wrote a book called “Tending the Heart of Virtue: How Classic Stories Awaken a Child’s Moral Imagination” (Oxford University Press, $33.33).

His goal was to build moral character, teach values, and instill important virtues in children.

The book gained a devoted following. Dozens of lectures, workshops, and requests to write another book of its kind ensued.

In the interim, Guroian’s children Rafi and Victoria became adults with children of their own.

In 2023, Guroian published a second edition with an expanded preface and conclusion, and some stylistic changes (Oxford University Press, $20.99).

His purpose remains the same and so, thanks be to God, does his stance.

He quotes Charles Dickens who, in an 1853 essay urged that “in a utilitarian age, of all other times, it is a matter of grave importance that Fairy tales should be respected.”

“Were Dickens alive today,” Guroian adds, “I do not doubt that he would protest the persistent bowdlerization, emasculation, and revision of the classic fairy tales.”

Guroian’s contention is that our classic children’s stories awaken the moral imagination by depicting the battle of good versus evil, showing the value of such virtues as honesty, truthfulness, kindness, and self-sacrifice, and issuing an invitation to embark on our own lifelong quest for beauty and truth.

The stories touch as well on universal archetypes: dark, strange, mysterious, and often frightening presences that hover on the edge of childhood consciousness: sex, for example; or conflict between parents; or adults that we see or sense are disordered in various ways, by addiction, moral weakness, physical disabilities.

Today’s commentators, grounded in identity politics, would subject fairy tales to “sensitivity screening” and gut the stories of all interest, shock, rough edges, and juice.

Hans Christian Andersen’s “Little Mermaid,” for example, willingly lays down her life for the human prince she loves (while the prince, oblivious to her sacrifice, goes off and weds another). In so doing, she achieves the immortality for which she has always longed.

The Disney movie spins a happier gloss, ditching the dark tone in favor of a lighthearted happy ending. Given the power to kill the prince, the Little Mermaid abstains, willing his happiness over her own. Contemporary critics disdain her oblation as the mark of a brainwashed, oppressed-by-the-patriarchy female.

Such critics miss the flaming glory of the soul’s longing for God. In fact, as Guroian notes, “The Little Mermaid invites great pain and suffering upon herself. That is because she imagines more for her life and is dissatisfied with the limitations of life under the sea.”

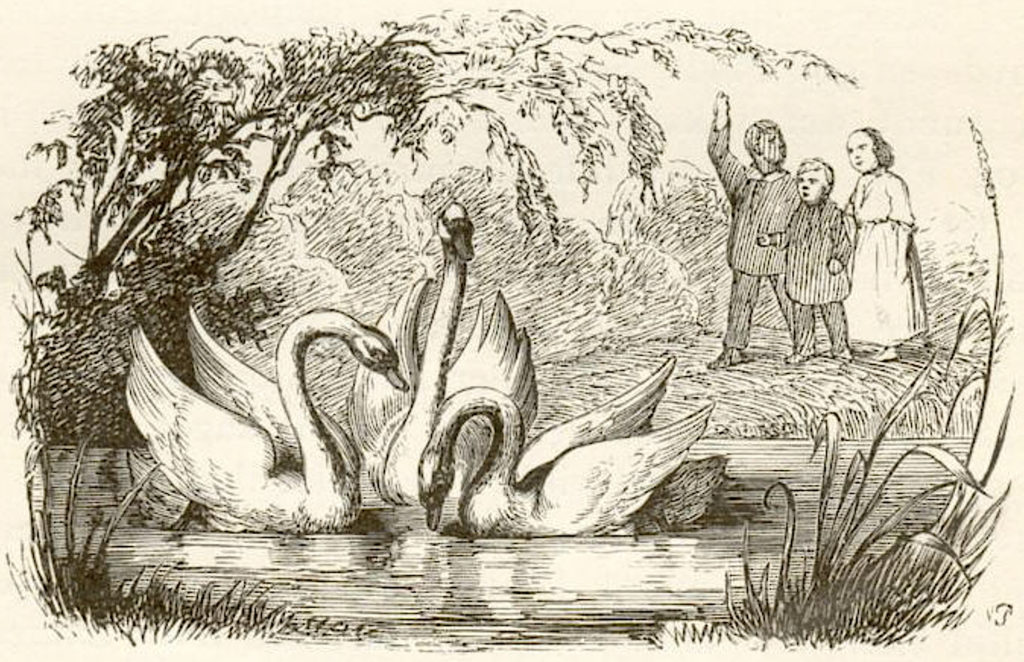

Andersen revisionists would analyze his fairy tales through the lens of supposedly repressed homosexuality. “The Ugly Duckling,” for example, has been “mercilessly bowdlerized and recast” as a tale decrying the bullying of underdogs. “This is wrong,” says Guroian. “ ‘The Ugly Duckling’ is about how a love of beauty can change one’s life.”

Guroian is right that children have a deep, ingrained notion of justice. I think they also instinctively recognize, and instinctively revere, the notion of sacrifice. And they definitely understand the terror of being abandoned, rejected, ostracized, cast out from the herd.

What makes fairy tales and fables so stirring is that the protagonist, whether he or she knows it, is on a hero’s quest.

The young heroes of these classic stories make mistakes, take wrong turns, and commit sins (Pinocchio’s lying; Edmund’s betrayal of his siblings in “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe”).

They’re presented with temptations.

They learn the abiding treasures of friendship (“The Wind in the Willows”). They meet elders who guide, prune, and form them (George MacDonald’s “The Princess and the Goblin”). They meet elders who want to destroy them (Andersen’s “The Snow Queen”).

They suffer, often for long periods of time, often physically and almost always emotionally and spiritually. They learn that the more intense our longing for connection and love, the more in a sense we are set apart from our fellows, many (if not most) of whom do not share our longing.

But over time, and through the suffering, they mature. They grow in love. They become flesh-and-blood humans. They may die, but they will also live into eternity.

In Dostoevsky’s “The Brothers Karamazov,” the dreamy Alyosha observes “that there is nothing higher, or stronger, or sounder, or more useful afterwards in life, than some good memory, especially a memory from childhood, from the parental home … some such beautiful sacred memory… is perhaps the best education. If a man stores up such memories to take into life, then he is saved for his whole life. And even if only one good memory remains with us in our hearts, that alone may serve one day for our salvation.”

We all have such moments from our childhood that have attained iconic status, that have stuck with us, that we return to again and again.

C.S. Lewis, remembering his own childhood, spoke of a feeling kindled in him as he gazed from the nursery window, a kind of “longing,” or sehnsucht. Sehnsucht, notes Guroian, “entails a sadness due to the absence of that something, as well as a ‘remembering’ and ‘recovering’ of it. Sehnsucht’s object is something one deeply desires and wishes to be joined to, and yet from which one feels removed.”

That’s the feeling classic children’s books engender in us. In childhood, as now, many of my own best memories revolve around reading — and writing — stories.