Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), Italian poet and moral philosopher, authored “The Divine Comedy.” His three-part journey through hell, purgatory, and paradise, with the Latin poet Virgil as his guide and the ethereal Beatrice as his muse, is perhaps the greatest work ever written on romantic love.

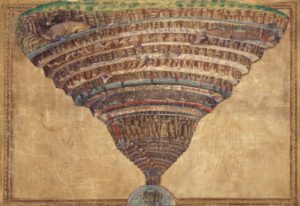

Dante started the “Inferno,” his description through the nine circles of hell, in 1307, five years after he was exiled from Florence on politically motivated corruption charges.

Reams have been written about this iconic poem: Dante’s innovative jettisoning of Latin in favor of the Italian vernacular, the terza rima (third rhyme) that makes translating so fiendishly difficult, the debates over which of the 109 and counting English translations has remained most faithful to the text.

What we do know is that the poem was inspired by Dante’s first encounter with the real-life Beatrice Portinari on the streets of his native Florence, possibly when he was only 8 or 9.

In “Religion and Love in Dante: The Theology of Romantic Love” (Kessinger Publishing, $18.95), Charles Williams describes her effect on him like this:

“The heart, where (to him) ‘the spirit of life’ dwelled, exclaimed to him, at that first meeting: ‘Behold, a god stronger than I, who is to come and rule over me.’ The brain declared: ‘Now your beatitude has appeared to you.’ And the liver (where natural emotions, such as sex, inhabited) said: ‘O misery! How I shall be disturbed henceforward.’ ”

Heady stuff — but if you’re anything like me, you’ve read the “Inferno” a few times, mesmerized by its gruesome punishments, and more or less skipped over “Purgatorio” and “Paradiso.”

Enter PBS with a fantastic two-part, four-hour documentary film called “DANTE: Inferno to Paradise.”

The series puts this epic poem, almost universally regarded as one of the pinnacles of Western literature, in historical, theological, political, literary, and very human perspective.

Through images, music, dramatic reenactments, voiceover, and commentary from scholars around the world, we learn of Dante’s childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood.

He entered into an arranged marriage and his wife bore four children, but Beatrice — who had also married, and died in 1290 — never left his mind nor heart.

Exiled under penalty of death from his beloved Florence in March 1302, Dante would roam impoverished, mostly about Italy, for the rest of his life.

At first, he hoped the vast poem he had in mind might both confirm his greatness as a writer and grant him reentry into Florence.

But when the “Inferno” was published and circulated around Florence, by 1317, instead the powers-that-be — many of whom were skewered in its verses — were enraged. Dante’s exile was now final and complete.

Christianity had always conceived of heaven and hell, but purgatory was in a sense Dante’s invention. Did such a place of purification exist? If so, where was it? What was it for? In imagining such a place in the afterlife, the series observes, Dante had a huge influence, however indirect, on the development of Catholic doctrine.

Good Friday marks the beginning of Dante’s journey through hell; “Purgatorio,” the penitential leg of the pilgrimage, starts on Easter Sunday.

While hell is static, frozen, utterly stagnant, “Purgatorio” is conceived as an ascent up a mountain with its souls in constant movement.

When he finally reaches the top of the mountain, Dante is faced with walking through the walls of purifying flames through which every other traveler must pass. Beatrice awaits him on the other side, Virgil reminds him. So he braves the fire and, in “Paradiso,” meets her at last.

Just as in real life, the long-anticipated meeting doesn’t go entirely smoothly — but if you want to see how things turn out, watch the series, then read all three parts of the poem.

“The Divine Comedy” can be interpreted many different ways: as a journey from sin to redemption; as an attempt to resolve the conflict between erotic and spiritual love; as the movement from fearful ego-based possessiveness to the transformed consciousness that at last allows us to know the “love which moves the sun and the other stars.”

However you read it, Dante laid down his life for it. His truest abode became the poem; the poem became his destiny.

As a human being, as an artist, and as a follower of Christ, he saw that his vocation was to continue to speak the truth — and so he did, and does, for us.

By 1321, the narrative of the poem and Dante’s life had converged almost completely. Hollowed out by the rigors of exile, and of writing, he completed his masterwork at last.

In September, he made an ambassadorial mission to Venice at the request of his patron, contracted malaria, and died.

Florence almost immediately regretted its mistake and tried to reclaim its native son — though it took the city council almost 700 years, until June 2008, to rescind the death sentence of arguably the greatest poet the world has ever known.

In “Dark Wood to White Rose” (Morning Light Press, $34.95), Dante scholar Helen M. Luke observed: “The man who wrote the last canto of the ‘Paradiso’ knew that we can never come to this vision by any shortcut. We cannot bypass the experience of hell; and still less can we evade the long struggle of purgatory, through which we come to maturity in love.”

Or as the series concludes: “Dante meant the poem to change our lives. Your life matters. Take care of it.”