Boomers. Millennials. Gen Z. The names used to classify some of the major age groups of Americans come up in academic studies, social media posts, and everyday conversations — but also in talk of “generation wars” that try to explain certain divisions in society.

To some, the differences between those categories — and the conflicts they provoke — are overblown. But to people like psychologist Jean Twenge, they define who we are more than we think.

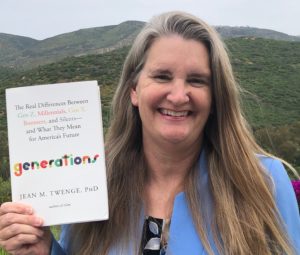

In fact, Twenge — best known for her work helping the public understand the correlation between screen use and mental health issues in younger Americans — has recently come to a bold conclusion.

“When you were born has a larger effect on your personality and attitudes than the family you were raised in does,” writes Twenge, professor of Psychology at San Diego State University, in her latest book, “Generations: The Real Differences Between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents—and What They Mean for America’s Future” (Atria Books, $32.50).

Why is that so? Twenge believes that the technological developments of the last century have shaped recent generations more than cultural or political events, contradicting a popular view among scholars.

On one hand, Twenge argues, these advancements have led to increased individualism and a slower life strategy: Technology has made it possible for people to focus more on their freedoms, choices, and identity.

At the same time, it’s led people to have fewer children, usually later in life, with the expectation that they will grow up slowly. In other words, things like biology and mortality have become less formidable obstacles to shaping one’s values and priorities.

From a religious standpoint, the data might seem threatening: Technology now has answers for human needs that people once turned to God for, like health or financial security.

But the data suggests that today, mental health, materialism, and marriage are Americans’ greatest pain points, and that the advances of the last 100 years have increased that pain, rather than alleviated it.

For people of faith — especially Catholics — alarmed about their well-being and future generations, can faith succeed where technology has failed?

The big picture

Take, for example, the “Baby Boomers,” the children of parents who lived through World War II at a young age and who, growing up in an age of remarkable technological progress, have enjoyed a quality of life never before seen in any prior generation.

And yet, Twenge claims, that “for their entire life cycle, Boomers (born 1946-1964) have been less happy, have had more days of poor mental health, were more likely to suffer from mental distress, and were more likely to be depressed than “Silents” (the generation before them) the same age. Between 2000 and 2019, the rate of Boomer “deaths of despair” skyrocketed: fatal drug overdoses increased by a factor of 10, deaths from alcohol abuse rose by 42%, and suicide by 60%.

Boomers’ struggles could be related to economic issues, like the disappearance of manufacturing jobs, the rise of income inequality, and the expectation that jobs should be personally fulfilling, Twenge acknowledges in “Generations.”

But another theory is possible. While mid-20th-century innovations like television and birth control opened up new possibilities and furthered the civil rights movements, they also ushered in a type of individualism which Twenge says brought “less stable relationships and the tendency to expect that self-fulfillment [would] bring happiness.”

In short, Boomers’ sharp inward turn has left them feeling alone and unsatisfied, which also extended into their married lives.

Twenge notes that Boomers expected marriage “to go beyond duty to satisfy the highest of expectations for sexual pleasure as well as companionship.” For that reason and others, they divorced in droves. The only reason the divorce rate has slowed since is because fewer people are getting married in the first place.

Today, more than twice as many Boomers are divorced than their parents were at their same age. Because Boomer men were less likely to remarry than both their female peers and their parents, the number of older men living alone has increased. This group plays a major role in the “epidemic of loneliness,” which now plagues the U.S.

How are younger generations faring?

While Gen X’ers (born 1965-1979) have been characterized as cynical, pessimistic, depressed, and distrustful, they have demonstrated one sign of hope, which is a higher birthrate than their parents’: despite marrying later than any previous generation, having premarital sex earlier, and uncoupling childbearing from marriage, Gen X women had between three and four children on average.

But their personal lives have not always been focused on others. “Since they were small children, Gen X learned from their Silent and Boomer parents that the self came first,” Twenge writes.

As the first generation to grow up with television and reach young adulthood during a period of economic growth, they were influenced by materialism in a way previous generations had not been.

Twenge notes that college-educated Gen Xers were more likely to pick career paths based on extrinsic rather than intrinsic values. In other words, they were motivated more by making a lot of money than “developing a meaningful philosophy of life.”

While their rates of adult suicide are lower than Boomers, the premium they’ve put on material goods and wealth has yielded high levels of self-reported depression and dissatisfaction.

The next cohort, Millennials (born 1980-1994), were very happy as children and teens but report high levels of depression as adults.

“Born in an era of reliable birth control and legal abortions, to mostly Boomer parents, Millennials were the most planned and wanted generation in American history to date,” Twenge writes. “Raised in a time of optimism, they had high expectations for themselves.”

Their development from childhood to adolescence was marked by economic growth and a focus on their enrichment and self-esteem. Their maturation also coincided with the adoption of the internet, the move to online shopping, and the proliferation of social media and streaming.

While Millennials were the most educated in American history, two downstream effects of all that schooling were delayed marriage and childbearing. Millennials report that they are waiting to marry and have a family until they have the resources they feel they need to support them. Paying off school debt, building financial stability, and acquiring assets have become precursors to settling down.

They also report that their desire for independence, leisure time, and the ability to focus on themselves is preeminent. Children are viewed as competition for fulfillment, rather than a source of it.

Twenge notes that even cohabitation among Millennials is down, and that today, 1 in 5 Millennial women will likely not marry, with that number inching closer to 1 in 4.

While most Millennials escaped adolescence without social media, the consumerism it urges plagues their adulthood: “Social media and TV showcase those at the very top of the income distribution (or at least those who appear to be at the very top), giving a skewed view of others’ income,” Twenge writes. “The result is called relative deprivation — a feeling you’re not doing well compared to others even if, objectively, you are.”

A lonelier future

Finally, social scientists are beginning to consider Millennials’ depression in light of their disaffiliation from religion. Religious practice has been linked to higher rates of happiness, given that it provides a sense of meaning and belonging.

While many hoped Millennials would return to religious practice when they began raising children, they have not. Sadly, many are discovering that friends and coworkers do not provide the same loyalty and stability that marriage and religious communities do.

Isolated and stuck on an earning-potential treadmill, Millennials are running out of steam.

The final generation that Twenge examines in depth, Gen Z (born 1995-2012), stands downstream of all of these generational changes which came before them. Their saturation by technology and individualism is manifesting itself in previously unimaginable ways.

Twenge says that Gen Z’s generational personality is best understood by the common parlance they use — language which is “tech-infused with notes of gender fluidity and anxiety.”

Twenge said that most Gen Z’ers she interviewed for her previous book in 2015 were skeptical about transgenderism, chalking the burgeoning idea up to confusion. But eight years later, Gen Z has embraced a new philosophy about gender — and has coaxed older generations along with them.

As of 2022, the number of Gen Z Americans identifying as either transgender or nonbinary was more than the population of Phoenix. Like other social scientists, Twenge is confident this is not a result of greater social acceptance of a naturally occurring phenomenon, but part of a generational shift marked by “rising individualism.”

“If people are all unique individuals, then it follows that gender identity is a choice — and people should not be restricted to two choices,” Twenge says. “People should be able to decide which gender group they identify with — or even reject the notion of a gender binary completely.”

Twenge says that the increase in transgender identification between 2020 and 2021 alone “suggests the change is accelerating.”

Despite rising numbers of Gen Z’ers identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (including preteens), Gen Z is significantly less sexually active than older generations. While the prevalence of pornography could have a role in this, Twenge thinks the shift from in-person socialization to online interaction could also have a big role.

While Twenge’s previous research delved into the data on how smartphone and screen time has left Gen Z delaying adulthood, concerned with physical and emotional safety (including restricting speech which they find offensive), and underprepared to read social or emotional cues, social scientists now have the data to connect screen time to skyrocketing rates of depression, anxiety, and suicide.

Gen Z’s abysmal mental health has been making headlines since before the COVID-19 pandemic. Most alarming to social scientists and others is their rate of self-harm and hospitalization, including preteens.

While Gen Z is gaining attention for their activism around issues like gun violence, climate change, and racism, Twenge isn’t sure they’re capable of provoking vast social change like the Boomers did. It’s possible that their pessimism, nihilism, and general hopelessness about their prospects in the world may dampen their effectiveness and stamina.

As a generation that is reporting the highest levels of disinterest in marriage and childbearing and the lowest recorded rates for both, what comes after them is anyone’s guess.

A ‘come to Jesus’ moment?

Of what use is this research to the Catholic Church, which is experiencing a generational crisis of its own right now?

For the last two years, Pope Francis has overseen the ongoing “Synod on Synodality” — a worldwide listening exercise aimed at fostering a more collaborative approach to church governance and evangelization between clergy and laity. This October, bishops and other synod delegates gather for a monthlong, closed-door meeting in Rome to be followed by a final one next October that will put concrete proposals before the pope. Francis is expected to respond with an apostolic exhortation sometime thereafter.

However, the input from the synodal process so far has been largely subjective. Could it also benefit from acknowledging findings like Twenge’s, which offer an objective look at the generational trends shaping society and might illuminate opportunities and sharpen priorities for evangelization efforts?

The Church has long promoted the antidotes to the worrisome trends Twenge outlines: It is better to give than to receive; you should love your neighbor as yourself; a man should leave his father and mother and cling to his wife — and they should be fruitful and multiply. A meaningful, happy life is one which is given away in service to one’s family or vocation and typically oriented toward eternal salvation.

Now more than ever, the Catholic Church has social science on its side to back up what it has long preached.

When addressing the mental health crisis, clergy and laity should boldly unmask the false promises of individualism. While Catholics should champion civil rights and promote and protect the dignity of the human person, attention must also be paid to the communal aspect of the human experience. Parishes, schools, and social services should lean into the work of developing communities in which people know one another’s names and needs.

Psychologists are better understanding how our culture’s emphasis on constant self-reflection — how we are feeling, what people think of us, who we are and how we present ourselves — is directly related to increased rates of anxiety and depression. The loop of self-analysis and need for feedback is taking a toll.

“Happiness scholar” Arthur Brooks of Harvard University has suggested removing or limiting the literal and figurative mirrors in our lives, including social media, to help get our mind off of ourselves and onto others. Besides being a spiritual truism, thinking about other people and outside of ourselves is also a mood lifter.

As for materialism, the Church has no shortage of wisdom and saintly examples which reveal how detachment from wealth, sharing with the less advantaged, and prioritizing eternal matters produce happier and healthier individuals and societies.

But perhaps most importantly, research like Twenge’s confirms the need for Catholic laity — and clergy — to encourage young men and women to get married, and find ways to better accompany them throughout their married life.

Studies led by Harvard epidemiologist Tyler J. VanderWeele have found that marriage yields lower levels of loneliness, higher levels of meaning and purpose, higher levels of affective happiness, and lower mortality — all reminders that encouraging and accompanying men and women in married life is some of the Church’s most important work ahead.

If secular experts like Twenge are right, and things like our birth year and what devices we use shape who we are, then their findings also prove that advances in technology and personal freedom haven’t made us happier.

For an institution that’s been helping people find the meaning of life for 2,000 years, that suggests our 21st century “generation wars” could prove to be the ultimate blessing in disguise.