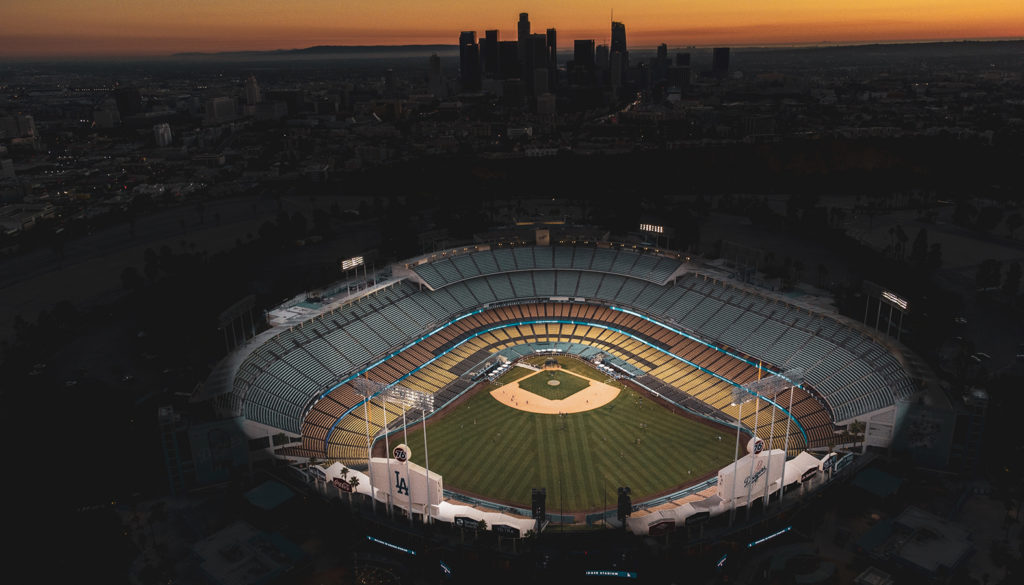

My streak of 57 years attending a Los Angeles Dodgers’ game every year might be coming to an end.

I started following the Dodgers around the time I made my first Communion in May 1965. I was an unlikely fan.

My dad was a second-generation Italian who worked around the clock to keep his small flower business afloat, my mom a schoolteacher. Neither had grown up around baseball or sports in general. It was an older cousin who played Little League and collected baseball cards who got me interested.

At night, the famous voice of Vin Scully would come into my bedroom on a transistor radio hidden under my pillow. Through Vin, I learned all there is to know about the game, the Dodgers, and much of life itself. I began to “think in Vin” (in fact, I still do).

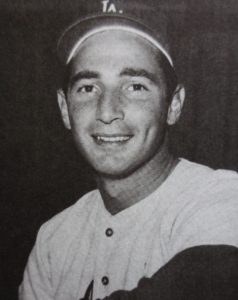

The Dodgers were very good in 1965. They battled the San Francisco Giants all summer long for the right to go to the World Series. Players like Don Drysdale, Maury Wills, and a midseason addition, “Sweet Lou” Johnson, led the way. But there was one player who stood out more than any of them. He was Sandy Koufax, a left-handed pitcher who threw easy, smooth, and hard. On Sept. 9, Koufax pitched a perfect game against the Cubs. I stayed awake until exactly 9:46 p.m. to listen to Vin Scully describe it. Ultimately, the Dodgers won the National League pennant and would play the Minnesota Twins in the World Series.

But something was amiss for Game 1 of that World Series. Sandy Koufax would not be able to pitch. He wasn’t hurt, so what could be the reason? The game, we learned, coincided with Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year for Jews. Sandy was Jewish and he chose to honor his faith. I was more worried about how his absence would impact the Dodgers. “He chose God over a game,” my mom explained to me. “That is the way it’s supposed to be.”

The Dodgers did lose the game that Sandy missed, but won the Series. Sandy pitched and won the deciding Game 7, 2-0.

My childhood love for baseball was also nurtured at a local park, where the boys of the neighborhood would play pickup baseball. It was the era of Sting-Ray bicycles, and we’d line our bikes up to form a home run fence on the field. Most everyone had a shiny Schwinn Sting-Ray. I had a Sting-Ray too, but it wasn’t shiny or a Schwinn: My dad had made it from an old frame he found in the trash on the way home from work. He bought a banana seat and high handlebars and spray-painted the bike green. The bike stood out from the others on the “fence.”

I didn’t mind. I liked my bike. But one day a group of junior high kids wandered through our game. They laughed at our fence, but especially my bike. “Look at this kid’s Sting-Ray,” one of them said. And then he got on it and rode it, giggling, to another corner of the park and dumped it on the ground. I had to walk and bring it back.

The bad feeling I had was not for myself, but for my dad. He had made my bike and was so happy to give it to me. I didn’t care that the boys were teasing me. I cared that they were disparaging my dad.

Those memories came to mind as I watched the controversy surrounding the Dodgers and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence in recent days.

The group has a history of anti-Catholic contempt going back to its founding in 1979. As a history compiled by The Catholic League has pointed out, the group’s antics have included holding a mock Mass using “holy Communion wafers and tequila” as well as a midnight “confessional” in a gay bar in San Diego. They’ve translated Catholic prayers in language too insulting to repeat. This past Easter, they put on a display in San Francisco featuring a person dressed as Jesus carrying a cross up a hill and then pole dancing on it.

These actions are undeniably blasphemous. The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines blasphemy as “speech, thought, or action involving contempt for God or the Church, or persons or things dedicated to God” (2148). Blasphemy is a sin against the Second Commandment.

Today, I feel much as I did all those years ago in the park. Just as that boy didn’t recognize the beauty of my lovingly made bike, it’s painful to witness people who don’t recognize the beauty of the Faith with which we worship God. In fact, they identify with a group whose very name is a slur to religious sisters and our Faith itself.

Our King did carry a heavy cross. He was whipped, insulted, and spat on. Over the 2,000 years since then, many of his followers have been persecuted, some put to death. Our religion is about all of these unusual and messy occurrences. It’s not pretty and shiny, either. But it shouldn’t be mocked by those who don’t understand it.

On Aug. 17, 1966, my dad took me to my first Dodger game. We sat on the top deck at Dodger Stadium. My hero, Sandy Koufax, pitched that night. He reinjured his troubled arm and had to come out of the game. Three months later he retired from baseball.

Since then, I’ve made a point of never quitting on the Dodgers in all the years since. I’ve gone to at least one of their games in person every season. In 2020, when the pandemic hit and fans couldn’t attend games, I thought my streak had ended. But when a few fans were allowed to attend playoff games at a neutral site in Texas, I hopped on a plane and attended to keep my streak alive. A New York Times reporter even met up with me and did a short article about my streak.

Now, I’m not sure what to do. I have continued to follow the Dodgers intently. I love baseball. I’ve already booked a trip and tickets to see the Dodgers in August, which would make it 58 years in a row.

But right now, I’m doubtful that I will attend. By honoring a group that has often mocked God and the Catholic faith, the Dodgers merit a protest.

After all, choosing God over a game is the way it’s supposed to be.