C.S. Lewis once said, “No book is worth reading at the age of ten which is not equally — and often far more — worth reading at the age of fifty and beyond.”

Lewis’ observation rang true for me while revisiting the Don Camillo books of Italian writer Giavannino Guareschi. I first read them at 13, but this rereading left me wondering what I got from him the first time. So much seemed new and insightful.

Guareschi was a journalist, writer, and cartoonist with a storied life. Born in 1908 in Northern Italy, he was unable to finish university because of his family’s financial difficulties. He worked for a newspaper, and as a gifted humorist, eventually wrote and edited for humor magazines.

One particular satirical piece got him in trouble, leading him to enlist in the Italian military in order to avoid problems with Mussolini’s government. After Italy changed sides and went to war with Hitler’s army, he was captured by the Germans and kept in a prison camp. He was offered his freedom in exchange for supporting the fascist regime in Italy, but he refused. After the war, he thanked God he didn’t hate anyone.

Once back home, he founded another humor magazine with monarchist sympathies. When the king of Italy was deposed and a republic declared, Guareschi, like most Catholics, backed the Christian Democrats in their struggle against the Communist Party, a narrow victory that was helped along by the pope himself.

Guareschi was part of the triumph of the “Democrazia Cristiana,” but soon became disenchanted with the politics of the official party. At one point, he was imprisoned for libel for publishing an attack on the prime minister of Italy.

The storyteller was a bit like Mercutio in Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” who wished “a plague on both your houses,” to the Montagues and Capulets. Steadfastly anti-communist, he nevertheless distinguished between the idealogues and the masses with sympathy for what they understood communism to represent.

He explored these tensions in the Don Camillo books. Guareschi created a fictional small town (a world, really) with a communist mayor, Guiseppe Peppone, pitted against the titular parish priest. The two, more alike than not, were locked in a comic battle of ideologies.

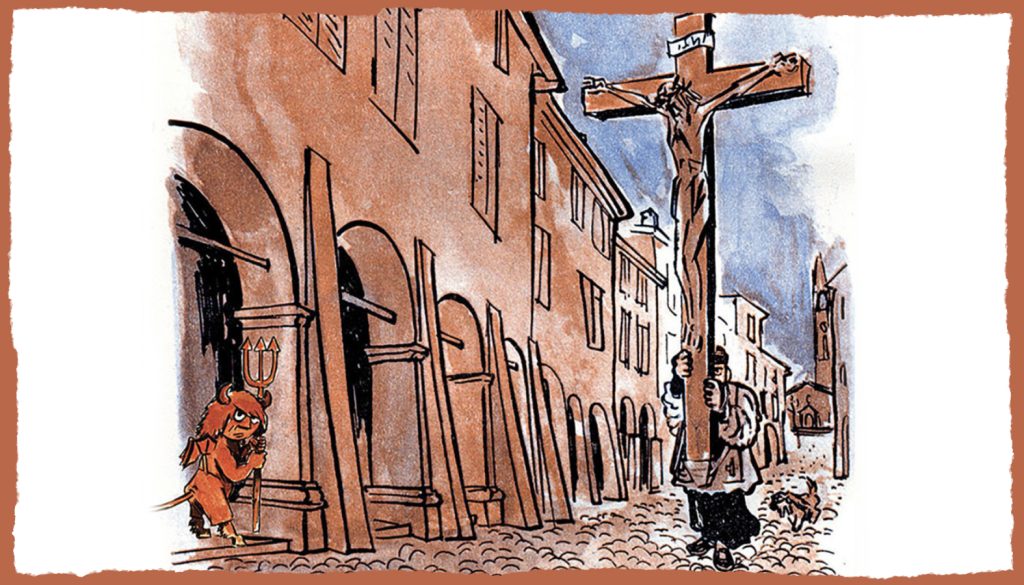

Guareschi was a humorist, a kind of Mark Twain of Italian literature, but one much more Christian and humane. As such, he presents Peppone as a hapless Marxist who has not abandoned his faith, but tries to hide it. Camillo is written as a feisty priest and a real scrapper, who is admonished by the figure of Jesus on the crucifix in the parish.

As someone who has been a pastor in a small town in El Salvador and as a survivor of disputes with various mayors, I appreciated this time around how Guareschi captures the comic-heroic aspect of the inevitable conflicts that arise in a town with many religious traditions.

At one point, Peppone and his men decide they will participate in the annual blessing of the waters of the river that passes the town and the prayer against flooding, but the priest will not permit them to march with the flag of the Communist Party. The communists retaliate by threatening anyone who accompanies Camillo in the procession. In turn, the priest tells some older folks not to come because there will be trouble.

Camillo goes alone, carrying the big crucifix in a harness as he marches down to the river. Peppone and his men stand in the way blocking the street. Camillo charges on, the men break ranks, and only Peppone remains. “Move out of the way,” the priest says. “I am moving not because of this priest but because of Him,” says Peppone gesturing to Christ on the cross. “Then take your hat off your fat head,” says the priest and continues on to the blessing.

In another tale, Peppone comes to church to light candles for his son who is sick, but won’t invite the priest to his house for fear that he will give his son extreme unction. At the time, that signaled that the infirm person was not expected to recover.

After hearing the doctor say the boy needs a medicine from the next town over, the priest commandeers a motorcycle and speeds to the hospital, saving the child. The owner of the motorcycle was hesitant, but the priest says, “If this child dies, I will break your neck.” I’m sure Camillo would have trouble with the political correctness expected in pastoral care in the real world, but his heart was in the right place.

Guareschi wrote the stories in a hurry, but they have the charm of folk tales. In another episode, the priest catches the mayor praying at the altar of the Blessed Virgin, lighting a candle in gratitude for winning a close election. When Peppone leaves, Camillo has one of his usual colloquies with Christ on the cross on the high altar. He complains about the hypocrisy of the communist thanking the Virgin for his reelection. Christ admonishes his priest to have more charity, but then it is revealed that Camillo also voted for Peppone.

The tales are ultimately about the secrets of a small town, but also the wonders of the heart of a priest who is a true shepherd of his flock. The dialectical conflict between Peppone and Camillo is submerged in the fellowship of the Church, the true community of the disciples.