From his first moments as pope, Benedict XVI established biblical renewal as a key theme of his pontificate. In fact, he spoke at length about “scientific” biblical interpretation during his homily for the Mass in which he was installed as Bishop of Rome.

This was unprecedented, and yet it arrived as a surprise to no one who knew the man's earlier work.

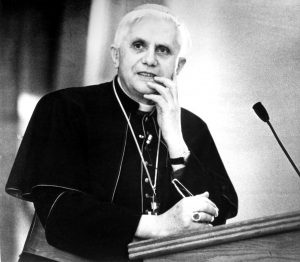

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger was a product of his times, and his times were tumultuous and productive in the sacred sciences. In the years of his priestly formation, the Christian world was enjoying a renewal of biblical studies. Many of its leading academic lights, both Catholic and Protestant, were active in Germany and writing in German. An intelligent seminarian couldn't avoid the conversation.

As he pursued advanced studies, he immersed himself in the biblical interpretation of the early Church Fathers as well as the medieval masters.

But his study of the sacred page was not simply an academic exercise. It informed his preaching, and it became a hallmark of his spiritual life.

He served the Church as a professor of theology and then as a theological consultant (“peritus”) to the Second Vatican Council (1962-65). In this role he helped to shape the council’s Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, “Dei Verbum” (“Word of God”).

“Dei Verbum” was the mature fruit of the biblical renewal. It was also a particular bugbear among the council fathers. It was debated intensely and redrafted repeatedly. Many historians credit Father Ratzinger as the greatest influence on the document's final form. And, more than any other document, “Dei Verbum” set the agenda for biblical studies and theology in the decades ahead.

After the council, Father Ratzinger returned to academic life, eventually taking a position at the University of Tübingen, which is renowned for its ecumenical faculty in theology. While there, he published the works that established his international reputation. In constant dialogue with his Protestant colleagues — and a very diverse Catholic faculty — Father Ratzinger developed skills and virtues that would serve him well as a scholar, bishop, Vatican official, and pope.

He learned to consider theological discussions from the Reformed position — and articulate a response in terms his interlocutors could appreciate. He gained a profound appreciation for modern methods of Scripture study and an admiration for the work of non-Catholic colleagues. He was able to find what was good and useful even in the works of those with whom he disagreed.

He published books and articles in many subdisciplines of theology: spiritual theology, fundamental theology, liturgical theology, historical theology, catechetics, systematic theology. He wrote a few specifically biblical studies, including an account of the Genesis creation narratives. But all his works bear a characteristic biblical stamp. He was fully engaged with the scriptural text and the history of its interpretation.

He was a biblical theologian.

Then he was a bishop, and then he was prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Yet always he worked as a biblical theologian.

In 1988 came a defining moment when he delivered the prestigious Erasmus Lecture. His address, “Biblical Interpretation in Crisis,” was eventually published as a book — and it became a manifesto for a movement. He called for a “critique of criticism” and a renewed appreciation for the hermeneutic of faith. For too long, Scripture study had been subject to the reductionist methods of the empirical sciences, and those methods had only limited effectiveness when applied to texts that are divinely inspired.

Some professionals, in both theology and biblical studies, found Cardinal Ratzinger’s address refreshing and even inspiring. Others vehemently opposed it. No one could ignore it, however, and it remained a matter of active and lively debate for decades.

The timing of his election in 2005 could not have been more perfect: As pope, Benedict XVI would be able to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the promulgation of “Dei Verbum,” the Vatican II text he had done so much to shape.

The celebration, begun in 2005, found its most complete expression five years later in the 2010 post-synodal apostolic exhortation “Verbum Domini” (“Word of the Lord”), which is arguably the most important document on Scripture produced by the Church in many years. It is a masterpiece, almost 200 pages in book form, and there are no weak words. While he affirmed “the benefits that historical-critical exegesis and other recently-developed methods of textual analysis have brought to the life of the Church,” he also said:

— “authentic biblical hermeneutics can only be had within the faith of the Church, which has its paradigm in Mary’s fiat. …”

— “the primary setting for scriptural interpretation is the life of the Church. This is not to uphold the ecclesial context as an extrinsic rule to which exegetes must submit, but rather is something demanded by the very nature of the Scriptures and the way they gradually came into being. …”

— “The Bible is the Church’s book, and its essential place in the Church’s life gives rise to its genuine interpretation.”

Here at last was a pope conversant in biblical Greek and Hebrew. It’s likely that no pope since Peter could match Benedict’s knowledge of rabbinic literature. And he was using these skills in powerful new ways.

In my opinion, he emerged as the great modern master of mystagogy — instruction about the sacramental mysteries and their rites. He renewed the art not only in its theory, in his official documents, but in his practice. His baptismal homilies have so far been neglected and are awaiting discovery.

His papal teaching was consistently grounded in Sacred Scripture, and this has appealed to Protestant intellectuals. It was Protestant clergy who founded the Joseph Ratzinger Society of Biblical Theology in the United States. And it was a Protestant publishing house that brought out “The Theology of Benedict XVI: A Protestant Appreciation” in 2019.

When he resigned his office, I was among those who deeply grieved at the silencing of his voice. Today my mourning goes deeper still.

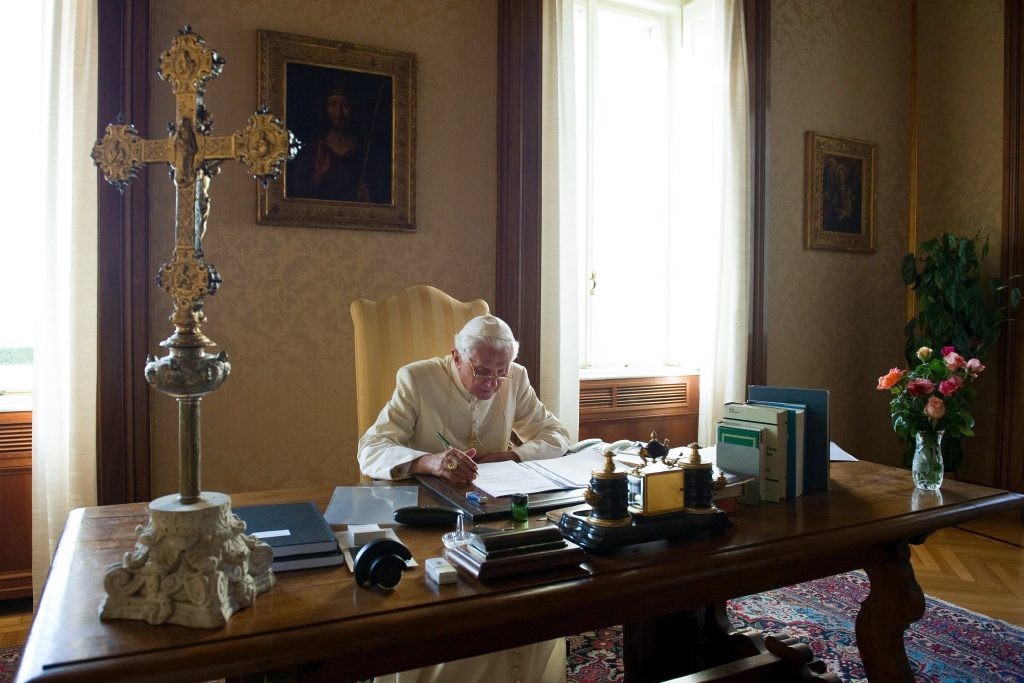

I know that in all his years as emeritus pope he was writing daily. I know that all his writing was profoundly biblical. So I wait in hope for some of it — any of it — to be published.

For it’s unlikely that we’ll see a pope like him for at least another 2,000 years.