Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993), an American artist, has been credited with restoring a sense of the sublime to late modernism.

He is also widely known as a “California” artist: a native of the West Coast who lived most of his life here, dividing his time as an adult between the LA and Bay areas.

Diebenkorn started out in the mid-40s as an abstract painter, firmly of his generation, and recognized early on as an artist of stature and integrity. In 1955, he suddenly segued, inexplicably to the critics and art world, into representational painting.

Until 1967, he did still-lifes, portraits, and landscapes. His work was both bold and sensitive. He did interesting things with perspective and planes. He liked windows. He seemed never to paint strictly what he saw, but rather what was going on in his head.

And then, in a move that could have been career suicide, he switched back to abstract painting — or switched to something new.

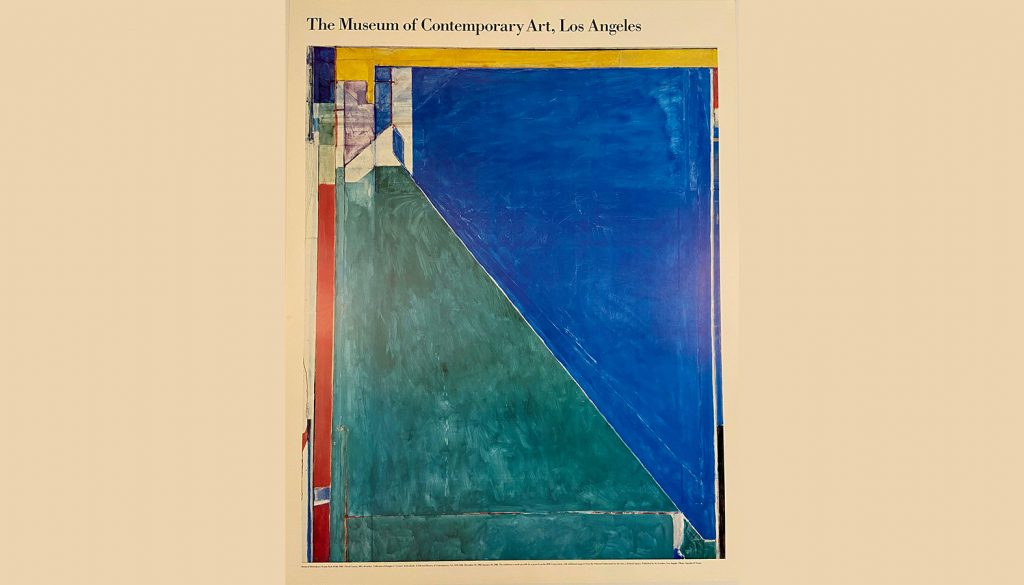

It was during this latter phase that he produced perhaps his best-known series: approximately 135 works that are known as the Ocean Park paintings.

Ocean Park is of course a neighborhood in Santa Monica that, at the time, was blighted, scruffy, industrial. Diebenkorn had a small studio there. But these were not, he insisted, landscapes.

He painted at first on huge canvases. Diebenkorn was a tall guy. His friend William Brice noted: “So many of the Ocean Park paintings run to the 6x8, or 7x9 feet. He could pop up on his little stool to reach the top. He chose a scale that embodied his own extension. That means something.”

And if they weren’t landscapes, they have everything to do with the inner landscape of anyone who’s lived for any length of time in Southern California, and particularly Los Angeles.

Diebenkorn was famously influenced by Edward Hopper and his paintings of existential angst. A sense of unease lurks in the Ocean Park shadows. But to me the series is also permeated by a generosity of spirit, a sense of humor, and a stubborn insistence on the light that shines somewhere perhaps very far within those shadows.

Take, for example, Ocean Park No. 140 (1985). It may not be a landscape, but its two triangular swaths of gorgeous saturated color — dark green and purple — to my eye irresistibly evoke land, sea, and sky. A band of persimmon along the left and another of a complex but cheerful deep gold across the top stirred the memory that every place I’ve ever lived in LA had a lemon tree in the yard.

“I attempt to make the lines and shapes right,” Diebenkorn commented. “One’s sense of rightness involves absolutely the whole person and hopefully others in some basic sense. What is important to artistic communication is only this basic part but if the artist doesn’t make his work right he has no idea what he has left out.”

That “rightness,” so apparent in his work, speaks of rigor, integrity, focus, and discipline. He eschewed “superficial grace.” “I want a painting to be difficult to do,” he said. “The more obstacles, obstructions, problems — if they don’t overwhelm — the better.”

Ocean Park may have been blighted at the time — but blighted in LA is somehow different than blighted in a place that’s colder, darker, not at the edge of the Pacific, and without LA’s outsized capacity for reinvention.

Here, the sun shines and the light pours down like a benediction even on blight. Here, what’s blighted today may in 10 years have resurrected into, say, an area of vibrant street life, murals, graffiti, and coffee shops: glitz cheek-by-jowl with grunge.

Ten years after that, the former blight will have morphed into blocks of sleekly homogenized “artist’s lofts” that neither you nor anyone you know can afford, and everyday folk have been priced out. But that’s LA, too.

So — not a landscape. But in “Cry of the Heart,” an essay collection on the mystery of suffering forthcoming in 2023, the late Msgr. Lorenzo Albacete writes: “To accept that we are protagonists in a cosmic drama is to break out of our material world and go beyond. This is a sign of our freedom. We will not settle for the notion that there is no meaning to life, that there is no drama, that we merely improvise. To believe that we are our own gods is an illusion, a denial of the reality of the existential meaning of life. But if we go beyond the material world for an answer to suffering, then we enter into a dialogue with the creator, and we are on the path towards transcendence.”

Speaking of which, what’s that interesting constellation of activity — that burst of small overlapping squares, parallelograms, and lines — in the upper left-hand corner of Diebenkorn’s painting? If we were standing on the lower right, we might gaze up that way for a glimpse of the sun or moon or stars.

I like to think that’s our story: my story, your story, the story of our time in LA, of our pilgrimage on earth, of the journey we will one day take to a realm that transcends landscape.