How many people in your life, beyond your own family, allow you to feel truly comfortable?

In 1963 I was 10 years old, having just moved to suburban Sacramento, 400 miles away from a San Fernando Valley home I hated to leave. But thanks to our transistor radio, I discovered a source of comfort and joy that I thought had been left behind forever.

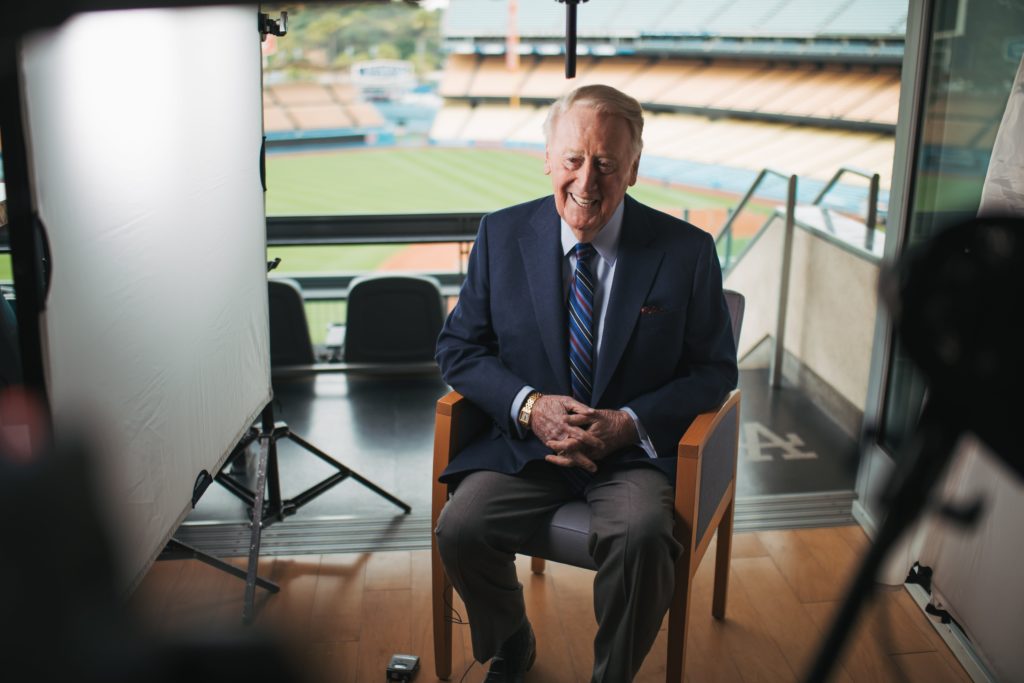

It was a voice, booming through the AM static, announcing a baseball game. Actually, it was the voice, greeting us with a friendly invitation, “wherever we may be,” to “pull up a chair” and spend part of whatever day it happened to be with him and our beloved Dodgers.

And what could be more comforting than the soothing tones and presence of a man who, simply by broadcasting baseball games, became part of our family — and everybody else’s?

Because Vincent Edward Scully was so much more than a broadcaster, albeit the best who ever lived. He was a friend, a colleague, a family member who welcomed you, invited you, chatted with you, engaged you, respected you, related to you, shared with you, laughed with you, commiserated with you.

He did that all while telling you about a game that — if you listened to him carefully — was simply that: a game. That whatever happened, life would go on afterward, and we could gather again the next night, or next season, to “pull up a chair” and spend part of an evening together.

Sometimes he would educate you, but never in a condescending, “I know more about this than you so shut up and listen” kind of way. Rather, he would share information that allowed you to appreciate a game, or a player, or a facet of life of which you were unaware — offering a perspective that broadened and enriched.

In any game, regardless of its significance.

Yes, his call of Henry Aaron’s 715th home run that broke Babe Ruth’s record — “Here in the deep south, a Black man is getting a standing ovation” — is a timeless classic. But some of my favorite “Vinny moments” are those that occurred in the late innings of a long-decided game.

Like in 2014, talking about the humanitarian works of Phillies pitcher Cliff Lee as he throttled the Dodgers on the way to a lopsided win. Lee and his wife, Scully pointed out between pitches, were parents of a son born with leukemia, had donated a large sum to the Arkansas hospital where he was treated, and were active in other charitable projects connected to youth.

“So that’s Cliff Lee,” Vin concluded, as Lee induced a harmless ground ball to end the eighth inning. “Quite a man — and quite a pitcher.”

And every Memorial Day, for Vin, was more than an occasion to celebrate baseball and barbecues. Early on in the broadcast, you could count on him to recall — with reverence, grace, humility and sincerity — the sacrifices made by Americans in wars throughout history, so that the rest of us could, indeed, gather together to celebrate baseball and barbecues.

Yes, Vin taught us so much over the years about baseball, and the Dodgers, and broadcasting. How, where, and why infielders are positioned as they are. Who, what, and when this or that Dodger luminary accomplished on or off the field. When to talk, or not to talk; what to say, or not say.

But as someone who began listening to Dodger broadcasts in 1959, I would suggest that Vin Scully’s true legacy and gift to the world is how he carried himself in life. He never presumed to be bigger or more important than the event, the sport or the team which employed him for 67 years; never considered himself more than ordinary; never thought of his work as particularly remarkable.

“God forbid I should become a prima donna” he told me when I interviewed him for The Tidings in 1992. “I’m just me chatting with friends, kind of laid back and easy-going.”

And yes, he was a lifelong Catholic, a product of New York City Catholic schools who never forgot the love and support from the sisters and priests who not only educated him, but helped form the man he became. He recalled fondly Mother Virginia Maria, his eighth-grade teacher, who encouraged his dream of becoming a sports announcer, and the Jesuits of Fordham Preparatory School, who lent him 20 pairs of shoes so he could be properly dressed for an oratorical contest.

Such generosity, he said, “certainly deepened my faith. And it also taught me a lesson about taking pride in how you comport yourself when you represent an institution.”

I had the privilege of interviewing Vin Scully three times: in 1986 for a long-extinct local magazine, and in 1992 and 2008 for The Tidings, the latter connected to his selection as a Cardinal’s Award recipient for 2009. On each occasion, he was as friendly, personable and engaging — as real — as he was on TV and radio, and when asked, spoke warmly and openly about his Catholic faith, and the perspective it gave to his life.

“I learned long ago that whether the Dodgers win or lose, it can’t affect my life,” he said in 1992, a year the Dodgers lost a record 99 games. “I think it has to do with faith, and one’s outlook on life. When you know there is meaning to your life, it keeps you going, and you can take things in stride.”

And yet he never wore his Catholicism or faith in God on his sleeve. He never preached it during his broadcasts. Rather, he practiced — over the airwaves and in his life — those character traits and behaviors that cannot and should not be defined by a particular religion: courtesy, respect, honesty, integrity, and simple common decency.

Traits and behaviors reflected in the words of St. James: “Let him show his works by a good life in the humility that comes from wisdom” (James 3:13).

In a world where static abounds and even suffocates, let’s allow the example of Vin Scully to resonate — and yes, to boom — in our lives.