Father Nathan Castle, OP, joined the Dominicans more than 40 years ago. For decades his focus has been campus ministry.

As he neared 60, he felt the urge to branch out in some new way. It was right around that time that he started having what he calls “night visitors.”

Between the hours of 2 and 4 a.m., people — most of whom had died violent or otherwise traumatic deaths — began appearing to him in dreams. He began writing the dreams down.

These visitations didn’t come out of the blue. As a boy in southeast Texas, he’d prayed hard for the souls in purgatory. The night after JFK’s funeral, as Nathan was saying his bedtime prayers, he “saw” the president, “all alone in a gray place.” Understandably, the man was in no mood to talk, but the two nodded to each other. John F. Kennedy has been a spiritual companion ever since.

The people who came to him, Father Nathan intuited, were stuck in some way. The vast majority of people who die — even hard, violent, or traumatic deaths — according to Father Nathan, pass easily into the afterlife. Maybe 5% don’t.

These people needed a little help, a nudge, some counsel. So he hooked up with a prayer partner — the first of many. The two would start by praying a “protective prayer” to the Holy Trinity, St. Michael the Archangel, Mary, and the saints.

Then they’d invite the person from the dream in question to “come in.” They’d wait, usually no more than a few minutes. And the person would begin speaking, sometimes through the prayer partner, sometimes through Father Nathan. He or she would tell their story, explain why they felt stuck.

The person might be angry — at God, the person who murdered them, or their parents. The person could feel guilty (a young Asian girl and only child who drowned in a tsunami after disobeying her mother’s orders not to go near the ocean). They could be ashamed of how they looked (a handsome man who’d died in a car crash that disfigured his face.)

Some souls were chatty, some circumspect. They seemed to know, at least vaguely, what they wanted. They were looking to move on somehow. Often they were looking for a companion to help them cross over to the next phase. They wanted to get rid of the anger, or hurt, or guilt, or shame, that was blocking them. So Father Nathan and the prayer partner would talk them through, or hook them up with another soul who’d passed over. They’d have a conversation with the person — 20 minutes, half an hour — which Father Nathan would record.

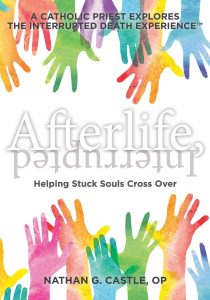

He collected many of these dreams and conversations into a book: “Afterlife Interrupted: Helping Stuck Souls Cross Over” (Bowker, $19.95).

Before including any given soul’s story, he always asked permission, which required a follow-up visit. These conversations with souls who were no longer stuck resulted in a second volume of stories and reflections.

The people who come to him are by no means exclusively, or even largely, Catholic. Which is fine — but I’m not the first person to note that Christ, or even God, barely figures in the stories.

“It’s a peephole,” Father Nathan says, “not a guided tour of the afterlife.”

What he and his prayer partners seem to provide is a kind of afterlife mental health triage, in line with the Church’s teachings on purgatory:

“From the beginning the Church has honored the memory of the dead and offered prayers in suffrage for them, above all the Eucharistic sacrifice, so that, thus purified, they may attain the beatific vision of God. The Church also commends almsgiving, indulgences, and works of penance undertaken on behalf of the dead… ‘Let us not hesitate to help those who have died and to offer our prayers for them’ (St. John Chrysostom).” (CCC, 1032)

Father Nathan is emphatically not a medium. He’ll help you grieve but he’s not the person to contact if you want to “get in touch” with a deceased relative, family member, or friend — an effort that would obviously be far outside the ambit of a member of the Catholic clergy.

He believes he has been given the gift of prophecy, to be exercised with love as set forth by St. Paul in 1 Cor. 13. He has the full approval of his provincial — for now — though the approval is by no means universal.

“I don’t want to be the guy with the one talent who buries it in the ground out of fear,” says Father Nathan. “I have a gift. I feel I should use it.”

When he was a boy about to make his first Communion, Sister Maximus told him, “God loves everyone and hears everyone’s prayers. But God especially loves children. Children’s prayers go straight to God’s heart.”

Whether or not we have the gift of prophecy, we can pray with a child’s heart each night before we go to sleep: for ourselves and for the souls of those who have gone before us.

Father Nathan faithfully maintains his own lifelong habit, formed in childhood, of praying before sleep. Compline — meaning “complete,” as he points out — is the last daily “hour” of the Divine Office.

It ends like this: “May the all-powerful Lord grant us a restful night, and a peaceful death.”