“For you created my inmost being; / you knit me together in my mother’s womb. / I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made; / your works are wonderful, / I know that full well.” — Psalm 139:13-14

“Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy” runs through July 10 at the Getty Museum. Presented in both English and Spanish, the exhibit explores depictions of the anatomy of the human body from the Renaissance through today.

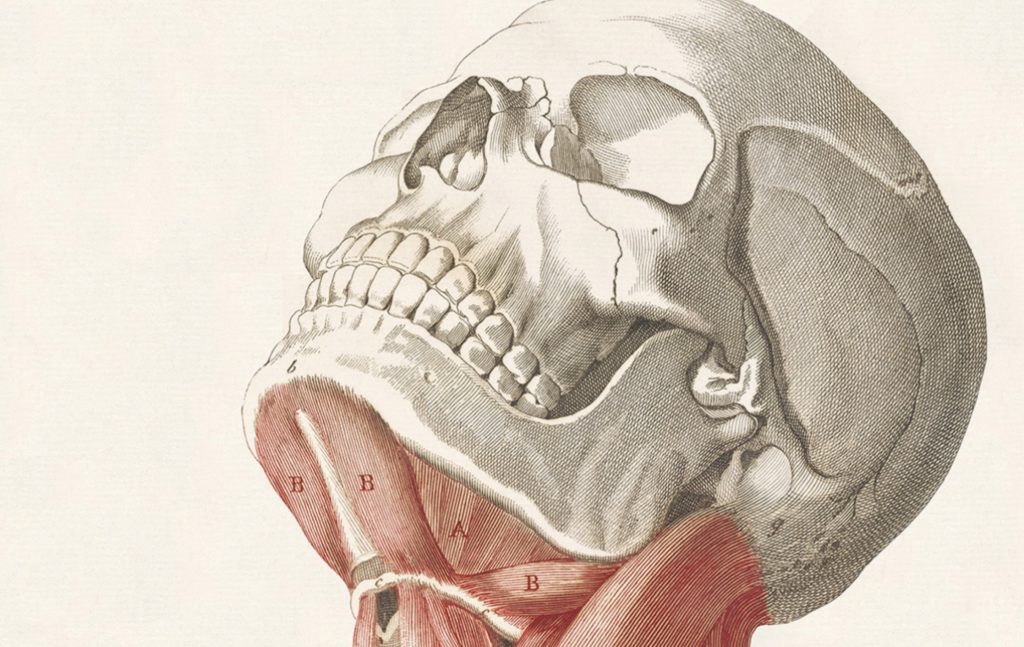

Included are anatomical images in a wide range of media, from Renaissance illustrations featuring delicate paper flaps that could be lifted to reveal the body’s inner structure, to drawings, engravings, woodcuts, mezzotint, sculpture, painting, and neon.

For centuries, artists were expected to have a firm grounding in anatomy; the structure of the human body was of paramount importance in both science and art. In fact, anatomists often hired their own personal artists in order to sketch the body quickly before decomposition set in.

Such an artist might focus on a specific area of the body: say, the muscles of the neck or eyelid. An abdominal dissection might spotlight details of the gallbladder.

Medical students at the University of Bologna in the late 18th-century could buy life-size anatomical prints from the shop of Antonio Cattani and his partner Antonio Nerozzi.

So could apprentice painters, who found the prints invaluable for drawing classes.

Three of Cattani’s life-size figures, based on sculptures by the Bolognese artist Ercole Lelli and comprising five joined prints each, feature in “Flesh and Bones.”

Many of the artists evinced a jaunty sense of humor. “Skeleton with Nerves” (1545), from an anatomy book published in Paris, holds its lower jaw aloft in order to show the viewer the entry and exit points of the nerve that travels through the bone. An array of indicator lines spring into space, lending the skeleton an air of macabre liveliness.

Such “dance of death” figures, the commentary observes, “remind the viewer of the shortness of life, the inevitability of death, and the wisdom therefore of living well but also piously before it was too late.”

In the 1616 engraving “Dissected Legs In a Landscape,” by Francesco Valesio, the skin from a pair of shapely, disembodied male legs is peeled back to show the muscles, bones, pelvic girdle, and lower spine. The parts of the body were lettered or numbered in such drawings, with an accompanying key.

Paduan anatomist Giulio Casseri’s posthumously published “Tabulae anatomicae” (1627) feature animated cadavers frolicking through landscapes of forests, lush vegetation, and waterfalls.

The colored mezzotint “Life-size dissected woman” (1750), by Jacques Fabien Gautier Dagoty (owned by the Huntington), depicts a nude woman: dark hair upswept, her gaze focused coquettishly at the viewer. Her upper right half, including a creamy bare breast, is comely and unblemished. The other three-quarters of her body presents as significantly less seductive: the skin has been cut away to reveal bundles of blood-infused veins, coiled intestines, and greenish internal organs.

The work might as well have been captioned “All Flesh is Grass.”

After that, things sped up. Stereoscopic photography, a 19th-century technology, paved the way for X-rays, which in turn led to today’s digital imaging and 3-D modeling.

More contemporary works include Realist painter Thomas Eakins’ “Wrestlers” (1899), “The Visible Woman,” circa 1960, a “Plastic model kit in a cardboard box” from the Renwal Toy Company, and “Robert” (2018), a suspended neon and glass work by Bahamian-born American artist Tavares Strachan, that memorializes Robert Henry Lawrence Jr., the first African American astronaut.

A $50 book of images and text accompanies the exhibition.

But to my mind it’s the earliest images that most compellingly evoke the wonder and complexity of the human body. People were closer to God then, more aware of the divine plan. Death was a part of daily life, not hidden away and sanitized.

Though the cadavers used for dissection in Renaissance times were generally those of executed criminals, for example, the GRI’s Monique Kornell reports that in 16th-century Italy, the souls of these subjects were still taken into consideration and cared for. “Lay confraternities would escort the condemned to their execution site, comforting them, encouraging them to repent, all the while holding religious images before their eyes for their contemplation.” The post-dissection remains would then be buried with an appropriate service.

Along the same lines, “The Child in the Womb” (1744) by Robert Strange (Scotland) is a life-size engraving of a disembodied female carrying a 9-month-old fetus. Everything’s in its place, the child like a nutmeat fitted perfectly to its shell: wet hair sleek against the tiny skull, miniature fingers furled, the plump, well-formed figure poised to exit the birth canal, burst into the world, and utter its first cry.

“For you created my inmost being; you knit me together in my mother’s womb. I am wonderfully and fearfully made.”

Three hundred years ago the artist captured the mystery and miracle of human life — as well as the fact that we all must die — in a way that today’s technology, no matter how sharp the image, can’t approach.

Set beside Strange’s drawing, an ultrasound — an image taken by a machine — seems to be missing a dimension.