People have a hard enough time remembering what was in the news 80 minutes ago, making it nearly impossible to paint an accurate picture of what the world was like 80 years ago.

I’ll be brief. In 1942 there was a world war raging. Americans weren’t sure at the time they were going to win it. All the things we take for granted, things like cars, tires for those cars, eggs, butter, and milk were either nonexistent or severely rationed. There was no television, and if a family owned a radio, it had the girth of a midsize Pontiac.

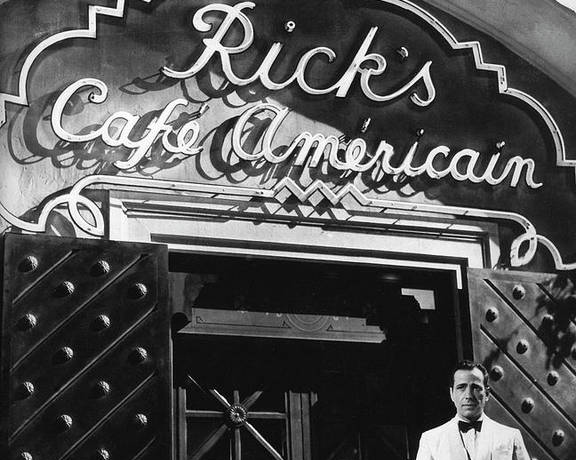

The movies then were a refuge and they reigned supreme. One movie in 1942 ruled over them all. The creators behind the now legendary Hollywood classic “Casablanca” did not set out to make history. They had a good premise for a story from an unproduced play with the pedestrian title “Everybody Comes to Rick’s.” When pre-production of the film started, Warner Brothers didn’t have a completed screenplay or actors to play the leading roles.

This was an era where every major motion picture studio had their own stable of stars, in much the same way as sports teams have rosters — which sometimes captured lightning in a bottle, pairing stars with screenwriters and directors for movie gold, and other times, creating profitable movie content but forgettable art.

After several starts and stops, and a proposed casting decision for the lead that would have condemned “Casablanca” to B-movie purgatory, they finally got it right. An unlikely romantic lead in tough guy Humphrey Bogart and a yet-to-be-star foreign actress Ingrid Bergman.

The story takes place in an exotic location made unvirtuous by the ravages of war and occupation. That war all those people in America were worried about is central to the movie’s narrative. The denizens of “Casablanca” have been turned into thieves, robbers, and killers in order to survive to see one more sunrise.

In this caldron is a simple story about love and loss. Bogart’s Rick Blaine has lost at a lot of things. He fought in a war in Spain and lost. He lost the country of his birth by some mysterious, probably illegal set of circumstances. Most important of all, he lost the love of his life, the beautiful Ilsa, who abandoned him during the evacuation of Paris.

Ironically, Rick owns a nightclub and casino where he supports himself on other people’s losses. He seems resigned to living strictly for himself, locking out the rest of the world. He finds an absurdity in the guise of a martinet Nazi major and a sly Vichy French officer, played wonderfully by the great Claude Rains. But when the woman he loves and lost reappears in that nightclub as a married woman, things get complicated and Rick becomes the sum of his resentments.

The movie is beloved for so many great scenes, tightly written and beautifully delivered. I will resist the temptation of spouting the “Casablanca” litany. But the longevity of this film goes beyond catchphrases and great craftsmanship. The entire film hinges on what Bogart’s Rick is going to do with the power he possesses in the form of much sought-after visas.

Those visas put the lives of the woman he loves and her husband in his hands. Rick lives in a world where power is everything — from the Nazi major who wields it and the French officer who cozies up to it.

It is obvious Ilsa still has feelings for Rick, and it is even more obvious that Rick has the power to steal this woman from her Nazi-fighting husband. The audience is never sure what Rick will do until the end.

And what he does in the end makes movie history. Who would have thought that a formula movie would have its climatic scene tilt on a fulcrum of virtue? The character who was so self-absorbed, so detached from the crazy world he inhabited, not only performs the ultimate Christian act, he does so without it coming off as maudlin.

The screenwriters of “Casablanca” owe St. John the Evangelist a shared screen credit. “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13). He not only gives up his life for the woman he loves, he rejoins the world. The ripple effect of these actions by the cynical American causes the cynical French officer, who had made an art out of weaponizing avarice and perfected bureaucratic corruption, to reevaluate his own shortcomings.

Ingrid Bergman never understood the pull of the movie. “I made so many films which were more important, but the only one people ever want to talk about is that one with Bogart,” she said once.

It is sometimes a stretch to chisel profound religious facets out of movies that were made primarily to put backsides in seats and sell popcorn. What Ingrid Bergman missed, and what the audiences have proved for 80 years and counting, is that there will always be space in everyone’s heart for virtue, and the hope that we all may have the courage to embrace it, whatever the cost.