Geoff Dyer is a British-born, LA-based writer with four novels and numerous nonfiction meditations on subjects that range from Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s cult classic “Stalker” to the photographs of Garry Winogrand to an inside look at life on an American aircraft carrier. His latest work, out in May, is a reflection on greatness in aging called “The Last Days of Roger Federer.”

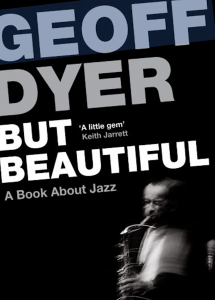

But my favorite is “But Beautiful,” a lyrical, semi-biographical, semi-imagined “novel” of some of the greatest jazz musicians who have ever lived: Ben Webster, Charles Mingus, Lester (“Prez”) Young, Bud Powell, Chet Baker, Thelonious Monk.

Duke Ellington, one of the few who didn’t burn out before his time, is in there.

And so is Art Pepper (1925-1982), West Coast jazz alto sax player, who was born in Gardena, played the Central Avenue clubs during their 40s and 50s heyday, and lived for years on Fargo Street in Echo Park. He spent three years at the since-discredited drug rehab Synanon, at the time in Santa Monica.

“Straight Life: The Story of Art Pepper,” his autobiography, was written with Laurie Pepper, his third wife. Pepper’s parents were violent alcoholics. His childhood was marked by trauma and abandonment.

But he seems to have been born with the kind of meteoric gift that borders on the supernatural, and he discovered music early. He made his recording debut in 1943 with Stan Kenton’s band. He was movie-star handsome, the epitome of cool.

Outside of the music, however, as critic Gary Giddins points out in the Intro, the reader is hardly “primed to admire Pepper, who whines, justifies, patronizes, and vilifies.”

The amount of alcohol, drugs, barbiturates, and street drugs Pepper ingested was staggering. He did four stints in prison, the last two in San Quentin. Somewhere along the line he proudly declared that he wanted to live and die a junkie. At 53, at Kaiser Panorama Medical Center, he did — ostensibly of a stroke.

And along the way, in and out of prison, institutions, one-night stands, marriages; as he traveled the world by plane, bus, car, and depending on how broke he was, foot; he also formed himself, through several musical incarnations, by all accounts into one of the finest alto sax players of his, or any, time.

How did that happen? How did someone who seemed so seemingly morally weak and narcissistically disordered produce such sublime music?

Dyer’s theory about the noticeably shortened life span of many jazz musicians of the 1950s and 1960s — a period when the form reached heights possibly never to be achieved again — is that the work required such a tight-rope-walking, hair’s-breadth musicianship that they were almost destined to burn out early.

The lifestyle — drink, drugs, exhausting travel and hours — was part of it. But more to the point, night after night, two or three shows a night, six or seven nights a week, every single show they were called to improvise, to invent as they played, to go beyond themselves until “a reciprocal shiver” passed “through audience and performers alike,” until suddenly the music was “happening.”

In the 1982 documentary “Notes from a Jazz Survivor,” filmed shortly before he died, Pepper observed: “I would get sick to my stomach, four, five days before a gig. It’s like if you’re going to do something different, it’s really scary. And if you’re not scared, that means you’re not planning on doing anything different.”

To call oneself to the very highest level, in other words, required the holding of a certain kind of tension that very few human beings would be equipped to hold; that perhaps for Pepper, and many others, was not possible without drugs and alcohol to keep their nervous systems in check.

Dyer takes it a step further: “Now, in what [Pepper] knows as the last years of his life, he is able to achieve an absorption in the music so total he can routinely lose all sense of himself, play beyond and above himself almost automatically. Every note strains toward the consolation of the blues, and even simple passages tear at your heart like a great requiem. Aware of this, he feels almost certain of something he has wondered about, suspected, and hoped for a long while — that he didn’t squander his talent by getting as [wasted] as he did, that as an artist his weakness was essential to him: in his playing it was a source of strength.”

This isn’t to promote the pernicious lie that drugs are a prerequisite to good art. But I couldn’t help but think of St. Paul: “I boast of my weakness.” Is it not one of the greatest mysteries of the human condition that we are able to function, create, and love, not only in spite of our weaknesses — but in some sense because of them?

There’s nothing wrong with a clean life, technical proficiency, and musical excellence. But can we ever be excellent in the truest sense of the word without a hefty dose of suffering, humiliation, bewilderment, and failure somewhere along the line?

Or as Lester Young once said: “Yeah, man … but can you sing me a song?”