It’s a prison story of a priest subjected to all kinds of troubles and humiliations: strip searches, solitary confinement, screaming and banging from fellow prisoners on his cellblock; vicious letters from a neighboring inmate; an Islamic terrorist who chanted prayers; days and weeks without the Eucharist, breviary, or his Bible; and the callousness of the judicial process influenced by a biased media and public opinion.

These were a few of the sufferings endured by a cardinal of the Catholic Church, not in some distant past but in modern times.

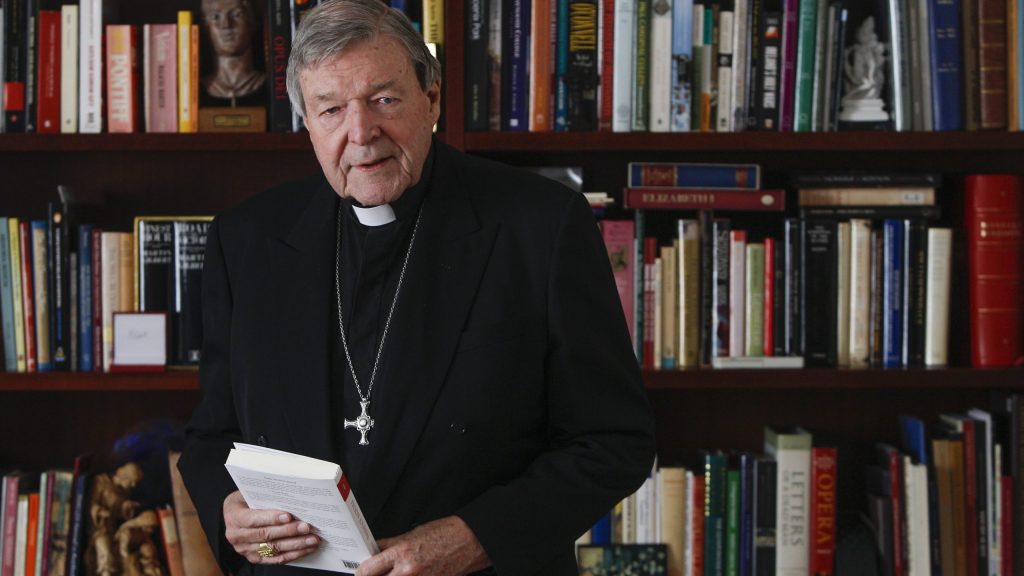

The story of Cardinal George Pell, who was eventually cleared of all charges against him and freed from prison in Australia, is told in his “Prison Journal,” published by Ignatius Press. Though its three volumes total more than 1,000 pages, I enjoyed keeping the cardinal company in the “clink.” (This phrase refers to a letter Cardinal Pell thinks was from a religious sister who said that if Jesus could be born where they fed animals, she guessed that it was appropriate a cardinal spend some time “in the clink.”)

Cardinal Pell’s volumes are marked with subtlety, insight, and reflections on living the Christian life behind bars. Mixed in with bleak details of the quotidian challenges of detention are beautiful reflections on the Scriptures, as well as ominous references to the appeals of his conviction and the reactions of others to them. Among those reactions was a letter from Ireland that tells him that a visionary said the Blessed Mother attributed his trials in Australia to his attempts at financial reform in the Vatican (though Pell admits being skeptical about private revelations, he had wondered the same thing.)

The cardinal offers many remarks about the state of the Church, including some painful insights. He is an astute observer of human details. For instance, seeing the word “home” scrawled on the windowpane of his cell prompts him to wonder about the man who wrote it “and whether he was bitter.”

“I suspect not,” the cardinal writes, “as this is my home for the moment and it is not a terrible place.” I am not sure I agree with his hypothesis, but I admire that he could consider it such.

Cardinal Pell is as adept at humor as he is with sincerity: He watches and comments on television preachers like Joel Osteen and the Singaporean Joseph Prince, keeping count of how many times they mention Jesus, the size of their studio audiences, and their couture (Reverend Prince has a great variety of rings and bracelets and Cardinal Pell is careful to observe the accessories). Nevertheless, he takes the messages of preachers and letter writers very seriously, and confesses his difficulty in forgiving some of his enemies. It is refreshing that the cardinal acknowledges that it is hard for him to grasp that God loves even those who attack the Church as much as he loves those who serve it, “but of course, that is true,” he writes.

I could not help comparing the three volumes to some other famous works about prison. The cardinal’s writings sent me to Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s “Letters and Papers from Prison,” for instance. Ironically, the “Prison Journal” also reminded me of “De Profundis,” written by Oscar Wilde during his imprisonment for a sexual scandal: although Wilde was guilty and Pell innocent, both convey the experience of a sophisticated intelligence shining a light on an environment and persons far from one’s ordinary life.

The first volume ends with the expectation of the results of the first appeal. The second deals with the Appeals Court confirmation of his six-year sentence. The third volume, entitled “The High Court Frees an Innocent Man,” kept me in a sort of tension of vicarious suffering, especially when the cardinal writes, “Today I complete one year in prison for crimes I did not commit.”

The entire experience gave him a great deal of compassion for his fellow prisoners. One of them wrote the cardinal a letter of support that reminded him of the Good Thief’s defense of Jesus. When the news broke of the overturning of his convictions, the prisoners in neighboring cells congratulated him and shared his happiness. The scene gives “Journal” a poignant touch of grace, especially because the cardinal believes one of those men was falsely framed for a life sentence.

Cardinal Pell was released from prison in April 2020 only to enter the restrictions of the initial COVID-19 lockdown. In a recent interview, the cardinal said his pre-Vatican II seminary prepared him for life in solitary confinement, while his time in prison prepared him for COVID.

I mentioned to a friend of mine that I was reading the “Journal.” “So, he was innocent?” he asked me and then said, “That’s good.” As Jonathan Swift said, “Falsehood flies and Truth comes limping after.” That is why these books are so important. Cardinal Pell, who wrote several books and countless columns in the course of his ministry, said the writing of this “Journal” was the easiest for him in terms of composition.

Thankfully, the “Journal” is an easy read, almost like having a tête-à-tête with a great shepherd of the Church. Ignatius Press should be congratulated on the project of publishing the writings, which will be an enduring witness to the present moment of Church history.