Five years ago, I began teaching a theology class at the University of Notre Dame on the sacrament of marriage. The student body of the class — which now attracts more than 250 undergraduates — are from all over the nation and world.

I began teaching the course because of a consistent decline in the sacrament of marriage in the United States. Fewer Americans are getting married, and those who do get married (especially Catholics) tend to wait longer to do so.

What I did not expect to encounter over these last five years is a new challenge raised by my students. More of my students are interested in marriage but are also more likely to avoid children. Last year, when asked how many of them were reluctant to have children, around 25% of the class raised their hands.

It is this fear of procreation, of becoming a parent, which is the real threat for Catholic family life in the United States.

This threat is not reducible to demographics. (Who will be Catholic if no one has children?)

Rather, the threat reveals a technocratic culture where the solution to climate change or financial precarity is not a renewed focus on the common good. It is a retreat into the self, a pessimism where the very goodness of the human species is questioned. Should human beings exist at all, or are we part of the problem? Is there a technology that can fix the problem of “us”?

Catholics must attend to this question directly, listening to those hesitant to have children. At the same time, they should make the case for what I call the “saving inefficiency” of family life, one that might be a catalyst for renewing the common good in social life.

Why people don’t have kids

My students generally give two reasons why they either want to limit the size of their families or avoid children altogether. First, they are concerned about having a child in a world plagued with a climate crisis, racism, and a polarized political community. How could they initiate a new generation into a world where there is so much potential for suffering?

The second reason is financial. Yes, I teach at the University of Notre Dame. Students at my institution are very wealthy. For the most part, they are far wealthier than I am or ever will be.

But they recognize that children are expensive. They are aware that the United States does not provide financial support for parents who have children. Yes, there are tax credits. But not a few citizens receive no more than 12 weeks unpaid leave upon the birth of a child, even within our Catholic school systems. Pew Research has noted that the United States comes in dead last among 41 countries, offering no paid leave for new parents.

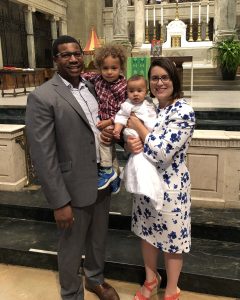

Not a few companies make up for this national policy by offering paid leave. My own university does, providing this benefit to both new moms and dads. But I live in South Bend, Indiana, where the average house costs $143,000. My spouse and I are perfectly capable of living in South Bend, owning a house, raising our two children, saving money, and enjoying a remarkable quality of life.

Not all my students can move to South Bend. Many will find themselves living in places like Los Angeles, New York, Boston, and San Francisco. The median house costs $900,000 in Los Angeles. New York and Boston alike come in around $700,000. San Francisco, worst of all, is $1.5 million.

If they get married, have kids, and move to a place they can afford to buy a house, they will likely have a commute. And those commutes could be two to three hours per day. None of this includes the cost of sending kids to a Catholic school, health care, and after-school child care (especially needed when both parents need to work).

My students, therefore, are not just being selfish. Yes, some of them confuse necessities (food and clothing) with luxury items ($1,200 Canada Goose jackets). But they recognize that families are expensive. And in cities like Los Angeles, keeping a roof over your head and food on your table usually requires that both parents work.

A Catholic apologetics for family life

What is the Church to do in these circumstances?

First, we must proclaim the goodness of life. Yes, the climate is likely changing. And that change is precipitated partially by human (in)action. Racism is real. And so is polarization.

But human life is good. This profession of faith is not exclusive to Catholics. Human beings are made for communion. The decision to avoid children because the world is fragile forgets so many beautiful dimensions of existence. Children teach us, as adults, how to live in the world as a gift. My children — the two we were blessed to adopt — have formed me to slow down. Life is not about speed or efficiency. Some problems can only be solved at the level of being. Of being with.

The real problem with the world is not too many kids. It is a technocratic paradigm — one that Pope Francis refers to in “Laudato Si’” (“Praise Be to You”) — in which all of life is reduced to profit, efficiency, and prestige. We have forgotten to be with one another. Stoically accepting the status quo is part of the problem.

We do not have a population problem as a nation.

We do have a cultural problem. Life is not purely biological but a matter of the good life, an existence lived in communion with other people. Life is ordered toward a common good, the flourishing of every man and woman.

Yes, life involves suffering. We can never promise any generation that we will eliminate all pain, protecting them from the precarity of the human condition. The COVID-19 pandemic has once again reminded the human family throughout the world of our contingency, even our own mortality.

None of this means that the world would be better off if fewer people existed. If we want to eliminate greenhouse gases, the problem may not be the number of children throughout the world but our almost idolatrous reliance upon technologies that produce these gases. Do we have the will to change, to live differently?

Here, I suspect it is the children themselves who may teach us a different posture toward life. Our Lord, in the Gospels, tells us to learn from the little children. Jesus Christ is not some starry-eyed romantic. He is one who points to the child because of the dispositions that the child possesses. The child is open to communion, not yet hardened by an idolatrous paradigm where life is reduced to profit, prestige, fame, or fortune. The child is happy simply being.

The fewer children we have around, the fewer chances we have to learn this saving lesson. Children are sacramental signs of hope. Despite the weaknesses of humanity, we are made for something good; something very good.

My children teach me this fact. Despite the perceived importance of my job, of the workaday world where I must live, I am not reducible to this employment. I am Dad, who has a vocation to play pet shop and pony and wrestle. I am Dad, who is beloved not for his capacity to generate profit but because I am lovable — as my 4-year old daughter regularly reminds me every day as I leave the house.

Of course, the Church — in imitation of her Lord — is also not a starry-eyed romantic. Children are still expensive. And it is here that lay Catholics have a role to play.

We need to also advocate for a change in social structures that make it more difficult to have children. Affordable housing is a dire need in our communities. A way of providing paid family leave, at least substantial tax credits for those who have children, is a necessity. We cannot deny — in cities like Los Angeles — that cost-of-living affects the capacity for many families to live flourishing lives.

Now, not all of us will be able to lobby Congress or our governor to enact fairer laws. But most of us belong to parishes. We can create cultures in our parishes where children are welcomed. The babbling of babes and the screaming of toddlers at Mass should not be met with derision. The more parents feel welcome in our parishes with their kids, the more likely they’ll discover a community to support them in their decision to bring a family (larger than two kids) into existence.

The parish must understand itself as a family of families, one that helps meet the concrete needs of families. For example: Child care is expensive. So, why not arrange it so that those with more time in the parish volunteer time to watch children? Gratis. There are dozens of grandparents in every parish, often distant from their own kids, who would step forward.

Parishes have an opportunity to support life here, to become spaces where the financial exigencies of having children are mitigated by a communion of men and women baptized into Jesus Christ, who have learned from their Lord to welcome the little ones.