Bioluminescence is oceanographer Edith Widder’s great obsession.

Put simply, bioluminescence is light produced by a chemical reaction within a living organism.

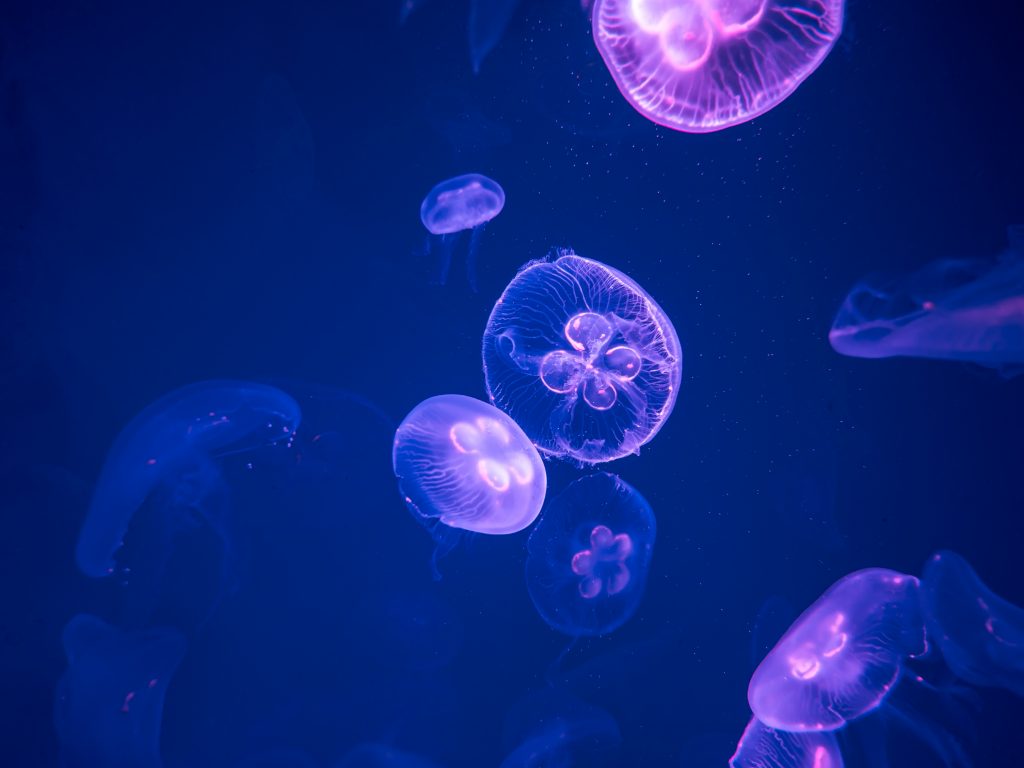

Fireflies and certain fungi aside, the vast majority of bioluminescence occurs in the ocean: fish, bacteria, and jellies, the most common forms of which are those creatures that float through the water with transparent bell-shaped bodies and tentacles.

There’s quite a bit of science in Widder’s new memoir, “Below the Edge of Darkness: A Memoir of Exploring Light and Life in the Deep Sea” (Text Publishing, $21). But you don’t have to be a scientist to be amazed and inspired by Widder’s life beneath the sea.

Born and bred in Massachusetts to academic parents, Widder was poised to become a biologist. But a spinal fracture, diagnosed during her college years, led to a surgery with complications that almost killed her and also rendered her temporarily blind. With amazing good humor, she emerged after four months flat on her back in a hospital bed.

“Fiat Lux” she names the chapter in which her sight slowly returns. Though she carefully refrains from labeling her recovery a miracle, it’s hard to miss the fact that out of this time of great personal darkness arose her life’s work, drive, and passion.

The die was cast: she’d become fascinated by light. She also became fascinated with the ocean, “a fantastically strange and wonderful place” and the earth’s last frontier.

We fund the exploration of outer space, while here on earth, by even a generous estimate only 5% of the ocean has been explored.

“In this world without apparent hiding places, the game of hide-and-seek is played out on a daily basis with life-or-death consequences.” Huge quantities of marine life hide in the depths during the day, below “the edge of darkness,” then, as night comes on and the darkness edges upward, swim nearer the surface for food.

In fact, this “vertical migration” that takes place in the ocean every day — the most common solution to the problem of no hiding places in a world of predators — constitutes “the most massive animal migration on the planet.”

Widder became “hopelessly addicted” to deep sea exploration in 1984, when during an evening dive off the coast of Santa Barbara she first went down in a metal diving suit called Wasp. At 800 feet, with the pressure bearing down at 355 pounds per inch, she witnessed a show of bioluminescence so dazzling that it changed the course of her life.

Bioluminescence is “cold light,” developed by creatures who need to survive in the dark. It most often manifests as a glowing blue, but can also be red, orange yellow, green, or violet. It can be used as a mating call, a warning, or a decoy, a signal to bigger predators to come and eat the predator that’s trying to eat you. It can be used as a flashlight or to temporarily blind an enemy. It can mean pain, fear, excitement. Scientists have wondered as well whether at times the marine creatures put on a show just for the sheer joy of it.

And what creatures! The velvet black dragonfish sports “a whiplike bioluminescent fishing lure protruding from its chin.” The stoplight fish is “a midnight-black beauty with a big red light organ under each eye and a smaller blue one right behind it.”

The saber-toothed viperfish has fearsome curved fangs so long and sharp that if they closed within its mouth, they would impale the fish’s brain: instead, they slide into grooves in the upper lip. A long fin grows out of its back and curves forward, “dangling a luminescent lure in front of its fearsome maw.”

The bioluminescence itself takes myriad forms. It can appear as a steady glow or a bright flash from a particular fish. It can make the entire deep sea look like a night sky full of stars. Swimming through a sea of sergestids, a type of deep-sea prawn with a body like cut glass and a cherry-red section behind its head, Widder catches her breath.

Each shrimp is illuminated from within by means of “two to four tiny glowing orbs held together in a chain by a gossamer sheath,” whose light comes on slowly and deliberately, as with a dimmer switch.

Another phenomenon to ponder: Down there in the darkest deep, a perpetual storm of marine “snow” falls: a mixture of fecal matter, decomposing plankton, and miscellaneous excreta.

Widder touches, but refrains from harping upon, the degradation of the world’s oceans, the tons and tons of waste dumped unheedingly in the sea, and climate change.

She prefers to focus upon hope. “We need a different outlook, one that focuses on our strengths, not our weaknesses. … Explorers are, by necessity, optimists who have to see beyond imagined limits to find a way forward. … They push past the scary monsters at the edge of the map and have the persistence needed to pursue solutions in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds.”

Or as a note pinned above Widder’s desk reads, “The world will not perish for want of wonders but for want of wonder.”