Shakespeare and Cervantes, Dante and Dostoyevsky. Their names are often associated with the “Great Books” of Western literature, works used in classrooms since the early 20th century to help form the intellects of young thinkers.

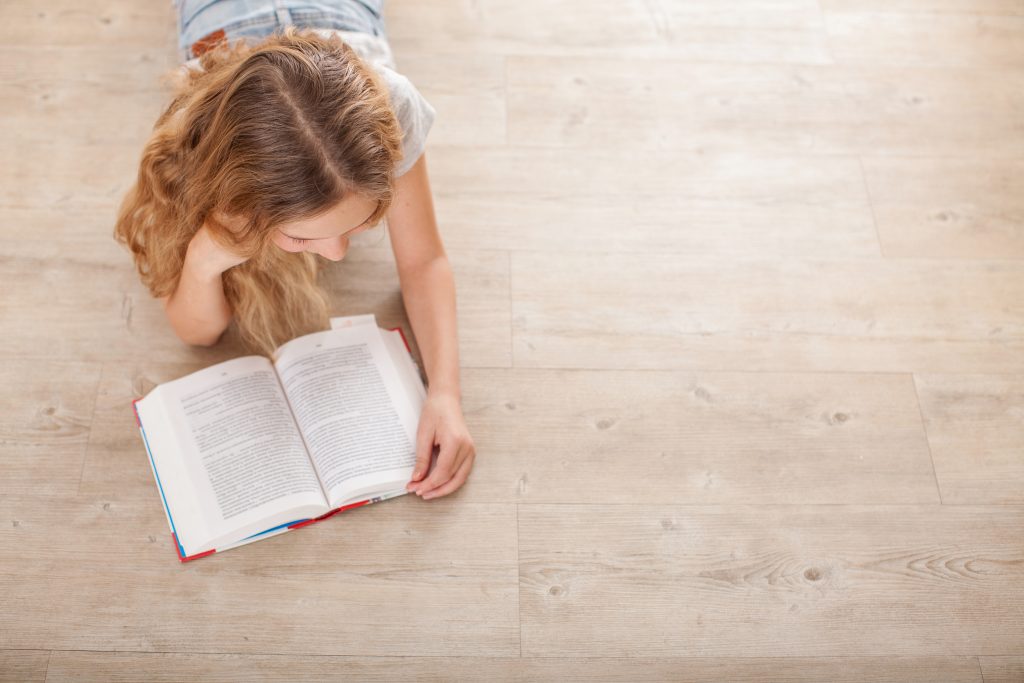

But what if a young student simply isn’t ready for Emily Brontë or Jane Austen? As Cheri Blomquist knows from experience, the effort to teach far above children’s reading and interest levels can backfire.

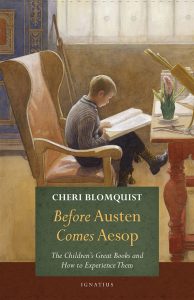

“When I was in 12th grade, I hit a snag in my lifelong love affair with books,” Blomquist, a freelance writer and teacher, writes in the introduction to her book “Before Austen Comes Aesop: The Children’s Great Books and How to Experience Them,” published by Ignatius Press ($17.99) in March.

That year in school, she found many of the assigned literary works too dense, complicated, or downright frustrating for her to appreciate. Are there any great books that can appeal to and edify a younger audience?

In “Before Austen Comes Aesop,” Blomquist makes the case for her own list of children’s great books, with tips on how to make the most of them. She spoke to Angelus about the book and how it can help students and educators.

What inspired you to write this book?

I’ve always loved children’s literature, and after I began teaching in local homeschool co-ops, I started paying attention to classes and programs for literature. I noticed that many literature programs were pushing kids only in eighth, ninth, or 10th grade to many, fairly heavy adult classics, like Dickens and Austen and Brontë — books that I was not ready to read at that age. I didn’t see how these kids could absorb all those books in a single year.

Then in 2013 or 2014, I read a book by Seth Lerer that was a children’s literary history, from ancient times to the present. It was kind of a dry, academic book, but I was very inspired by it and thought, “Wait a minute. If these books have been so important throughout history, maybe there is this counterpart to the ‘Great Books’ that are really the children’s ‘Great Books’ — the ones that have been the most important and have impacted children the most. What are those?”

And so I started on a journey. I was just going to share on my website with parents as I went, but it just got bigger and bigger.

In the book, you mention that you’ve tried to make the list as objective as possible. Could you talk a bit more about the importance of that objectivity and how you went about building the list?

There are a number of books full of recommendations for Catholic, Protestant, or secular parents to help their children find good books to read. I didn’t need to add onto that with my own opinion. I wanted to know what history revealed itself to be in terms of what literature was truly important. There are so many classics!

If you look at a literature program, [you wonder] why is this book read in this class, but not this [other] book? How do you choose? I wanted history to reveal to me what was truly important in the development of literary history and what was important in the lives of children from ancient times up until the modern times. So it was very necessary that I be as objective as possible. I did have to make judgment calls here and there, but that was something I only did when I felt that I had to.

One thing that’s important for Catholics and any Christians to consider is that because it’s an objective list, it’s not all going to be in line with our Catholic values. There was some discussion with my editor at Ignatius about whether to include a couple of books because I don’t want [the books listed] to look like recommendations. These are not recommendations. I put labels on some books saying, “Parents cautioned,” and one of them actually says, “Parents extremely cautioned!” So some of them may be troublesome [books] that parents need to be aware of.

In your own opinion, what are some of the best children’s books for kids to read, and why?

My favorite is “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.” That’s been my favorite since my 20s, but that would not be one of the most important books on my list; it’s not one of the foundational ones. The foundational ones are ones that, paradoxically, we tend to think of as the adult classics as well, because actually the greatest books cross over.

Those works include Homer, Aesop’s fables, the Greek myths, King Arthur legends, and “Robin Hood.” I have a list in the back of my book for parents who don’t have a lot of time and want to focus on the most important ones. “Pilgrim's Progress” is also very important, and then there are a few more modern ones, like “The Hobbit.”

We tend to think of children’s literature as just for young ones, as if they’re a stepping stone to the “real” literature. And that couldn’t be further from the truth! First of all, [when it comes to] great art, it doesn't matter who it’s for. Art is art. It doesn’t matter if it’s “Goodnight Moon” or Homer; it’s going to affect us differently, and it’s going to have different elements and features, but it’s still art. Second of all, some of the important adult literature has been embraced by children for centuries, like “The Odyssey.” So we have to stop thinking of it as, “This is for children, and this is for adults.”

“Before Austen Comes Aesop” is organized into various sections, from the detailed list of children’s great books to study guides and appendices. How would you recommend readers make their way through the book?

It depends on parents’ interests. It’s meant to be a reference book for homeschooling or for parents who just want to expose their children to the “crème de la crème” of classic children’s literature. In that sense, parents can use [it] according to what their needs are. But it’s also meant to be read in terms of the history, because the history of children’s literature is valuable in its own right.

Each section of the first part of my book describes what was happening in children’s literature during [a particular] era, so that there’s some context for the list of books that follows. That may give parents some orientation as to why these books were published when they were. For example, “The Water Babies” was published at a time when Darwinism and fantasy were the rage in Victorian times.

If I were approaching “Before Austen Comes Aesop” for the first time , I would be looking, first of all, to see what the children’s “Great Books” are because I’d be curious! But then I would think, “OK, if I’m going to teach my ninth-grader literature, I don’t want to invest in this $200 program. I think I want them to study “Alice in Wonderland.” It’s a good, solid book that they could handle; it’s at their interest level and at their reading level. So let’s dive into this one and follow one of the study plans. That would be one way to approach it in a logical way.

What impact do you hope “Before Austen Comes Aesop” will have on children and adults?

I want there to be a deeper respect for children’s literature. I feel like it is shoved aside too early and not taken seriously enough at the older ages of youth, [namely] preteen and teen years. It’s often considered superfluous in that [people think] it’s not important anymore and we need to move on to “Wuthering Heights.” We’re not taking time to read “Alice in Wonderland,” even though it’s one of the most important Western pieces of literature ever written!

I want people to access children’s literature more easily and more deeply, without having to depend on a curriculum or study guides with regimented questions. They can experience it in other ways, and they can do it themselves with their child.