Lately I’ve been reading a lot about “stuff.” How much of it we have, what we do with it while we’re alive, what happens to it when we die.

The latter is actually a big problem. In the olden days, people would pass down their heirlooms, furniture, and household goods and the recipients were thrilled to get them. But today no one wants a 12-piece dinner set, or a set of sterling silver, or a heavy oak table with eight dining room chairs.

To me, the point isn’t how many or few belongings we own but how much we love and care for them.

The problem is that very likely no one else cares for them. There’s a name for the favor you’re supposed to do your relatives and friends by getting rid of your belongings before you croak. It’s set forth in such books as “The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of Clutter” (Scribner, $16.99), by Margareta Magnusson.

Again, I get it — but there’s something peculiarly Western about the notion that your person, your belongings, and the space you inhabit are a burden on the rest of the world.

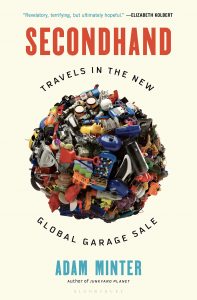

Adam Minter considers the “death cleaning” aspect of our belongings, and many others, in his book “Secondhand: Travels in the New Global Garage Sale” (Bloomsbury Publishing, $16.77)

Tammy Wilcox, manager of a Minneapolis, Minnesota, company called Gentle Transitions, makes a living clearing out the living spaces of people who have permanently moved on. “I went through pics of safaris, animals, his whole life,” she observes of one recently deceased gent. “I told his family they should take them. They said no. 1-800-JUNK came, and it broke my heart.”

Many people drive up from Nogales, Mexico, to the Tucson, Arizona, Goodwill stores daily to comb the wares and bring them back over the border. Though technically the practice is illegal, U.S.-to-Mexico second hand is a booming industry.

There are people in the U.S. who spend their workdays running old T-shirts and hoodies over the whirring blades of a machine specifically designed to make rags — rags being another (who knew?) huge business.

Minter travels all over the world: the U.S., Malaysia (his current home), Benin, Canada, Japan, talking to the people who wholesale, ship, and sort.

In 2016, second hand was a $16 billion industry in Japan. (People there often die alone and undiscovered for days if not weeks or months in their high-rise apartments, which gives rise to another niche business).

“Before the 1960s, Japanese had a feeling of “mottainai,” a difficult-to-translate Japanese word that expresses a sense of regret over waste, as well as a desire to conserve,” reports Rina Hamada, editor of Japan’s Reuse Business Journal. But that was before the living standard in Japan shot sky-high. Now people are way more acquisitive, though they’ll buy second hand if it’s of high quality.

Humongous warehouses around the globe house used goods destined for global shipments. Hamaya Corporation operates out of a small city 35 miles outside of Tokyo. Refrigerators and washing machines stacked three high are bound for Vietnam; pallets of knitting machines will go to Nigeria. Electric keyboards, PCs, boomboxes, chainsaws: the appetite for such goods is insatiable.

In Ghana, Minter learns that in some parts of the world used electronics and appliances fetch a higher price than new: the used items are often of better quality (because they’re older) and they’re more repairable.

In fact, the decline in quality of goods across the board is one reason for the enormous growth in the secondhand trade.

(Apple, by the way, purposely renders their products unrepairable, gluing them in such a way that they can’t be pried apart without destroying the phone or tablet; using screws that require a special, impossible-to-find screwdriver.)

Clothing, for example, is now universally acknowledged to be of such poor quality that it’s essentially disposable.

At Used Clothing Exports in Mississauga, Ontario, as much of one-third of the used clothing generated in the U.S. and Canada is sorted, priced, and shipped by “graders.”

Panipat, a town in northern India, is home to the world’s largest concentration of clothing recyclers.

The implications reach far beyond what we might grab from our closets any given morning. The secondhand clothing industry has almost completely wiped out the African textile industry, in particular the manufacture of kente cloth, the beautiful fabric that was once the pride of Ghana and its craftspeople.

But as Minter acknowledges, “Simplistic explanations built on what seem like logical correlations — used must undermine new! — don’t do justice to the complex, very human reasons that individual consumers make specific choices.”

German theologian Dietrich von Hildebrand observed: “All possessions … that have real value, that in themselves are honorable, excellent, significant, that fall like dew from above and ascend to God like incense, achieve a higher and new radiance in Christ.”

So I say hang onto the things you truly love. After you’re canonized, people will want the stuff for relics.