When I read the news in March about the passage of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, I reflexively winced when I saw that the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts were to receive $75 million each in relief funding.

With the spreading of the coronavirus (COVID-19) set to threaten the lives of the sick and elderly, throw the economic prospects of so many into flux, and rob me of time with my loved ones, I wanted as many resources as possible to be allocated to STEM fields with the hope that they would swiftly deliver us a therapeutic treatment or a vaccine.

Two months into this pandemic, I cringe when I think about my initial reaction.

It was always clear that we should and could prioritize the most pressing needs in the crisis: saving lives, healing the sick, protecting medical personnel, and finding a treatment and/or a vaccine.

But as someone with a Bachelor of Arts in Humanities, who has been an enthusiastic — some might say obnoxious — evangelist for the liberal arts, I should have thought more carefully about what else we would stand to lose if we lost language, art, and music, all of which help us to express grief, calm anxiety, and offer hope in turbulent times.

Philosophers, historians, writers, musicians, and artists have been active in these weeks and months of lockdown, and the engagement with their work by millions around the globe has demonstrated a real hunger for the fruit they bear.

As the health care systems in several countries began to be overwhelmed and ventilators were in short supply, ethicists found their role and voice in advocating against a zero-sum game in which the elderly were sacrificed so that the young might live. Among those was Charlie Camosy, assistant professor of bioethics at Fordham University, who has also been writing about the need to develop protocols so that COVID-19 patients do not have to die alone, nor in a manner against their wishes.

Historians have helped us to look at how Americans made their way through the 1918 pandemic as a point of comparison and instruction. In an NPR interview, medical historian Dr. Howard Markel, director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan, shared how epidemics are “living social laboratories,” which demonstrate how people behave before, during, and after such an event.

While social distancing was also implemented in 1918, he remarked how much easier it is for us to do because of access to the internet, which nowadays is key to shoring up economic prospects and keeping people informed.

When commenting on the question of whether or not life will go back to the way it was, he referred to the fact that after several waves of the Spanish flu, life not only came back but it “roared into the twentieth century.”

“That makes me positive,” Markel said. “I have faith in the ingenuity of the human mind and the ability to rebuild even from situations that seem quite disastrous and final. History tells us that happens.”

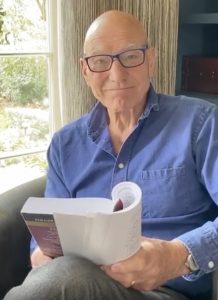

One of history’s more celebrated human minds, William Shakespeare, has even gotten a good deal of play during the pandemic. The Globe Theater in London is streaming his plays so that people can “virtually attend” performances of his works from their living rooms for free. Meanwhile, British actor Patrick Stewart is reading a “sonnet a day” on his Instagram account. Merely two weeks after he started, his posts had garnered more than 450,000 views.

“When I was a child in the 1940s, my mother would cut up slices of fruit for me (there wasn’t much),” he posted. “And as she put it in front of me she would say: ‘An apple a day keeps the doctor away.’ How about, ‘A sonnet a day keeps the doctor away’?”

Patrick Stewart reads "a sonnet a day" live via Instagram. (Image via Instagram @sirpatstew)

In a similar vein, world-renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma has been posting recordings of live performances on his Twitter account under the hashtag #SongsofComfort.

“In these days of anxiety, I wanted to find a way to continue to share some of the music that gives me comfort,” he wrote before posting his first piece, Antonín Dvořák’s “Going Home,” an apt choice for when the lockdown began.

He has dedicated some pieces to particular audiences: an Ennio Morricone composition for Italians in lockdown; the Sarabande from Bach’s Cello Suite No. 3 for health care workers on the frontlines; and even an original piece he performed with Mister Rogers in 1985 for parents and children in lockdown together. In addition to listening to Ma, we have taken to streaming the free concerts provided by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Boston Pops in our home.

Even Pope Francis has drawn on literary figures to make sense of the present moment. As a recent piece in Angelus discussed, the Holy Father has referenced one of his favorite novels, “The Betrothed” by Alessandro Manzoni, more than once during the lockdown. A former literature professor, Pope Francis regularly cites fiction in his writings and interviews. During the pandemic, he has used Manzoni’s epic tale set during the 1630 plague to make the case for turning the pandemic into a moment of conversion.

One silver lining of this crisis is that the arts and humanities have been made more widely available to people who might not have the economic means, good health, or time to access them otherwise. The treasures of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, virtual tours of the Vatican Museums, and nightly performances of the Metropolitan Opera, to name only a few offerings, are all just a click away.

We need a variety of fields to navigate our way through a global health crisis. They all deserve our support. Science and medicine are the disciplines that help to save lives — the humanities and arts help us understand why they are worth saving in the first place.