A visit to LA’s shrine to St. Pope John Paul II

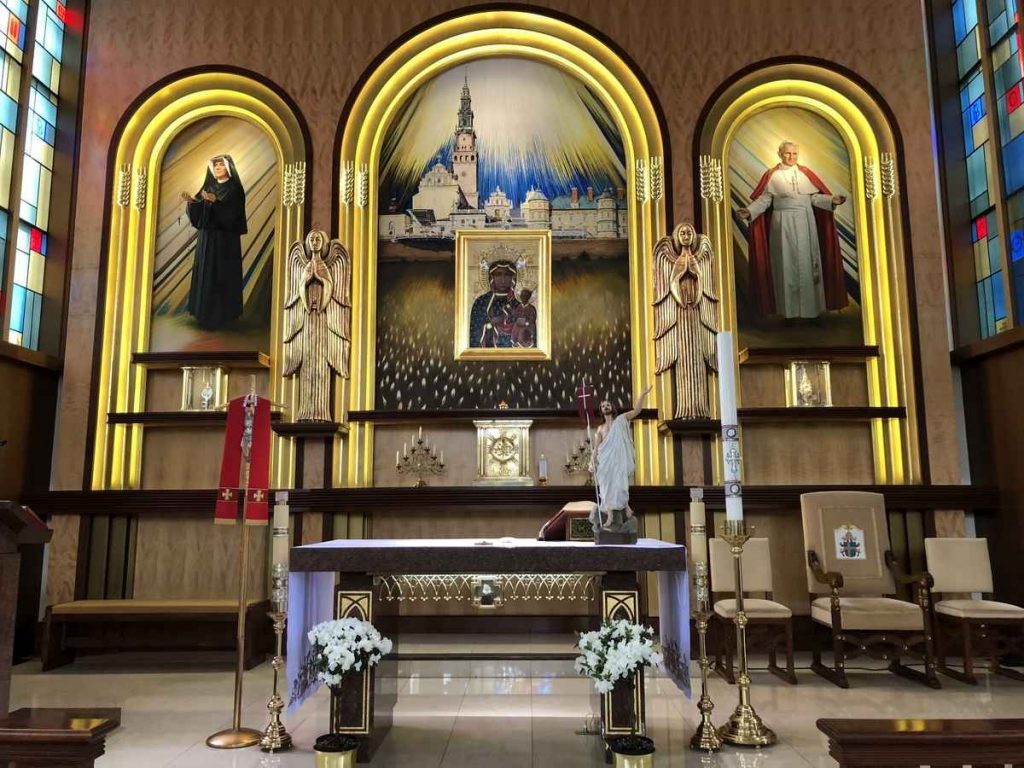

Our Lady of the Bright Mount Church, in the West Adams District, is the only Polish parish in Los Angeles.

On Oct. 25, 2015, Archbishop José H. Gomez declared it LA’s Shrine of St. John Paul II.

The shrine is only open during Mass, which is 9 a.m. and noon on Sunday, 8 a.m. on Monday, Thursday and Saturday, and 7:30 p.m. on Wednesday and Friday, with Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, devotions and prayers before (all are welcome to come and pray or sit in silence).

All Masses are in Polish.

Before making my way to the church for Pentecost Sunday Mass, I arranged to meet afterward with Sebastian Konarski, office administrator.

Then I brushed up on the history of Poland and studied the information on the church’s website:

Eleven-year-old Jadwiga, a “delicate young girl,” installed as queen in 1384.

The intrigue surrounding the image of Our Lady of Czestochowa, known to the Polish faithful as the Black Madonna.

The terrible suffering of the Polish people, first under Nazi Germany, then the Soviet Union, from the beginning of World War II until the 1989 establishment of the (democratic) Republic of Poland.

In front of the church, a cobblestone walkway, symbolizing the rockiness of the spiritual path, leads to a life-size bronze of St. Pope John Paul. Stone benches and rose bushes invite contemplation.

Inside, I took a pew near the back. That I was at a Polish Mass for Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit inspired the disciples to speak in tongues, seemed only fitting.

Father Slawomir Szkredka, visiting from St. John’s Seminary, presided. His clear gaze and gentle demeanor infused the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass with meaning as I followed along in my missal.

Afterward, Sebastian gave Father Szkredka and me a tour of the shrine.

First he explained that the pastor and shrine administrator, Father Rafal Dygula, SChr (Society of Christ), was in Chicago. “It’s because of him that the church was newly renovated, statues were placed and the relics are in place. The shrine would not be as it is now without him. His efforts have truly made it a place for pilgrims to come from everywhere.”

We learned that on Aug. 29, 1976, the then Cardinal Karol Wojtyła said Mass at Our Lady of the Bright Mount. The left front pew, farthest spot to the right, is reserved to this day for those who want to sit where the future pope sat, and to pray where he prayed.

The shrine boasts the first first-class relic of the pope to be issued to the U.S., a bit of hair that was installed beside the altar in 2011.

Mary is honored and glorified in a miraculous image of Our Lady of Czestochowa donated by the late Father Michael Zembrzuski, who established the Pauline order on American soil.

Also displayed is a first-class relic of St. Zygmunt Szczsny Feliski, SFO (1822-1895), archbishop of Warsaw, founder of the Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary and exiled in Russia for 20 years. There are first-class relics of St. Faustina (1905-1938) and of St. Faustina’s confessor, Blessed Michał Sopoko (1888-1975).

Amazingly, there’s a first-class relic of St. Maximilian Kolbe, the Polish priest who offered himself up to die in place of a fellow inmate at Auschwitz. As the saint was cremated, such relics are quite rare.

Sebastian and his wife found this one in the attic on church grounds. Before he was captured by the Nazis, Sebastian explained, Father Kolbe’s brother priests, knowing his holiness, shaved and kept some of his beard.

First-class relics: A tiny chip of bone. A strand of hair a few millimeters long.

I didn’t even try to pronounce the soon-to-be-canonized saint from whom the next relic had come, so Father Szkredka and Sebastian pronounced it for me: Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko (1947-1984), a Polish priest who supported the Solidarity trade unions and was martyred by communists.

“How did he…?” I asked.

“Kidnapped by three secret police thugs,” they murmured in reply. “Tortured. Savagely beaten.” “Still in his cassock.” “Could not recognize his face.” “Closed casket: They didn’t want his mother to see him.”

Father Szkredka, who from the age of 6 had known he would be a priest, grew up in Poland during the 1980s. “We knew they had come for him,” he said quietly. “And we were all praying for him.”

I suddenly understood a bit of what it must have meant to the people of Poland to have had a pope — the first non-Italian in 400 years — elected from their ranks; a pope who had been forced to study at an underground seminary because at the time the country was under Nazi rule; a pope passionate about human rights and credited by many for the eventual fall of communism in Poland.

I didn’t know a word of Polish, but I knew to kneel before Father Popiełuszko's relic.

As the antiphon for Mass had noted: “The Spirit of the Lord has filled the whole world, and that which contains all things understands what is said, alleluia.”