Before the sexual sin crisis in the church, popular culture was awash with unsympathetic and, I believe, generally unfair representations of lousy men of God. For quite some time, high-brow literature and the more mundane forms of popular entertainment have played a role in the in making the cleric as insipid broken man, closeted hypocrite, or sinister monster the gold standard.

Now it doesn’t help my argument at all that bishops and priests have been exposed lately, playing out all three of these roles in real life. But as disheartening as it is to have these non-fiction monstrosities piped into our living rooms on a daily basis, it still feels unfair that all priests and religious types are painted with the same broad brush.

Doesn’t seem to matter how far back you want to go. Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” has a rather unsympathetic portrayal of a cleric. The Monk in the Tales is no paragon of virtue to be sure. A more recent vintage of this is in the film “Elmer Gantry,” starring Burt Lancaster as a con man roaming the Deep South looking for a racket, which he finds in the tent revival circuit. The performance became a kind of blueprint for countless other portrayals of phony religious hucksters.

It is sad that the Elmer Gantry school of religiosity has become the pop culture norm and sadder still that real preachers are still making headlines going on television pleading to the folks at home to send in their money, so they can buy that Gulfstream G550 God, not the preacher, is insisting he have.

Despite so many (Catholic and Protestant alike) walking/talking clichés of hypocrisy, the data from reliable, non-religious sources say the general state of clerics within the Church is pretty good. Actually, it is very good. As horrible as the data is and stipulating one abused child or one damaged seminarian is one too many, the reports from the Boston and Los Angeles debacle from the early 2000s, to the most recent Pennsylvania Attorney General’s report, show the overwhelming number of priests and bishops in these dioceses were good men trying hard to uphold their own personal vows and shepherd their flocks.

Yet, the Elmer Gantry pop culture model lingers as many people are either violently angry (not without some cause) about all things clerical, or dismissive to the notion of religious expression, seeing all things like a Burt Lancaster con job inside a revival tent meant only to free the poor wretched souls inside from their hard-earned pay.

So naturally I tend to seek my solace in other medium of pop culture. Victor Hugo’s “Hunchback of Notre Dame” is like a lot of great literature. More people know the title than know the book. And those who don’t know the book but know one of the several cinematic renderings of the story don’t know anything about what Victor Hugo was trying to say. Won’t go into the gory details of the “true” story of the hunchback of Notre Dame, but suffice it to say, it doesn’t end nearly as “happily ever after” as the Disney version.

Claude Frollo is not a good guy. He is the Archdeacon of the cathedral of Notre Dame and he is a literary manifestation of a duplicitous “churchman” who presents a pious exterior while at the same time harboring impure thoughts about a certain gypsy girl. Hugo is not bashing the Church. It’s Frollo’s sin that is the problem. His position in the Church just gives him the power to act upon his sin… Hmmm, art imitating life?

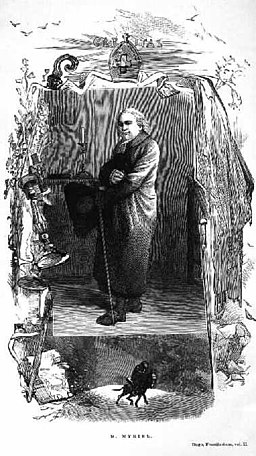

In his greatest work, “Les Misérables,” Hugo gives us Bishop Myriel, whose simple act of mercy at the beginning of the story saves Jean Valjean of life in a prison work yard, but has condemned innumerable high school English students to several hundred more pages of plot and character development.

This pious characterization of a good priest comes with a price though, and the writer used the character of this good man of God for a device made clear by the exchange he had with his son. Hugo’s son was a vehement anti-cleric and begged his father to make the man who saves Jean Valjean not a man of faith but a man of reason and progress. Hugo stuck to his original intent with a searing retort. “I cannot put the future into the past. My novel takes place in 1815. For the rest, this Catholic priest, this pure and lofty figure of true priesthood, offers the most savage satire on the priesthood today.”

Ouch. May we all, cleric and layperson alike, strive to close the distance between the fictional goodness of Bishop Myriel and our own true selves.

Robert Brennan is a weekly columnist for Angelus online and in print. He has written for many Catholic publications, including National Catholic Register and Our Sunday Visitor. He spent 25 years as a television writer, and is currently the Director of Communications for the Salvation Army California South Division.

Start your day with Always Forward, our award-winning e-newsletter. Get this smart, handpicked selection of the day’s top news, analysis, and opinion, delivered to your inbox. Sign up absolutely free today!