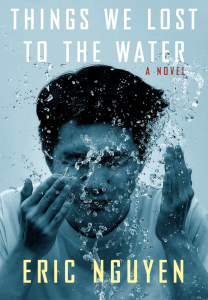

I was reading Eric Nguyen’s novel “Things We Lost to the Water” (Penguin Random House, $14.43) when the images of desperate Haitians hoping to enter our country via Mexico began appearing in the news.

I thought of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s line, “hecatombs of broken hearts,” with regard to the human tragedy the images portrayed, and of the Children’s Crusade, a historic and nearly forgotten human disaster on an enormous scale in which some young 13th-century Europeans launched a hopeless attempt to reach the Holy Land.

Nguyen’s perhaps overpraised novel has to do with Vietnamese immigrants to New Orleans. One of its fictional threads tells the story of a family leaving Vietnam to become “boat people” when the father suddenly decides to stay behind. His embittered wife writes persistently to her husband about his children, one of which was born in a refugee camp, and is finally answered by a letter saying that he doesn’t want her to communicate with him in the future.

For me, it was the image of several planeloads of Haitian men being deported to Port-au-Prince that resonated with the novel. Were families separated? Would those people ever see one another again after a wandering trajectory that took some of them through Brazil and Chile to our border with Mexico?

You don’t have to be an advocate of open borders, which I am not, to feel the human pain of the frustration of those people who came so close yet so far from realizing their illusory goal. Nguyen’s novel rather imperfectly attempts to give an accounting of the way the traumas of their immigrant experience played out in the lives of each of the family members who made it to New Orleans. Like some ambitious homilists, Nguyen seems to have had trouble finding an ending, but does so with a bang: Hurricane Katrina brings the family together — in a way.

I was reading the novel to compare it to “Afterparties” (HarperCollins, $21.99), a much-acclaimed collection of short stories by the son of Khmer immigrants from Cambodia, Anthony Veasna So, his first book released posthumously after his fatal drug overdose in late 2020.

“Afterparties” offers snapshots of the lives of Khmer who were resettled in So’s hometown of Stockton, California, and environs. It is a world of which I knew very little, of a people trying to make sense of their lives in a cultural context that is sometimes overwhelmingly alienating. It is a world of immigrants who are struggling, they run donut shops and specialty grocery stores, and their failures are mirrored through the consciousness of their partially assimilated children, orphaned of the traditional Buddhist culture and yet still strangers to a California culture heavy on drugs, fashion, promiscuous sex, and making money in whatever corner of the state they find themselves.

Both writers show a keen awareness of the many traumas in the lives of immigrants. Their books have some examples of nice writing, making it little surprise that both made former President Barack Obama’s reading list this year.

“What We Lost to Water” has a scene that recalls Dostoyevsky’s “Crime and Punishment,” where a young Vietnamese immigrant is asked to beat up a Chinese woman who runs a grocery store. The would-be Raskolnikov loses heart when the Chinese woman makes him some food because he said he was hungry.

There is a story in So’s collection about a woman so distraught about her daughter’s tragic death that she becomes convinced that a baby born to a relative is the reincarnation of her lost loved one. She arranges a celebration that includes Buddhist monks and a feast from which the deceased woman’s daughter attempts to flee.

Nguyen records another Buddhist ceremony, based on a Vietnamese tradition, of renaming the deceased so that he does not become a hungry ghost and return to haunt the family every time his old name is mentioned.

The novel and the short stories also offer frank criticism of the Communist regimes of Vietnam and Cambodia, which surprised me. In a time when a kind of false nostalgia for socialistic experiments seems to be making a comeback in this country, it is instructive to listen to the voice of immigrants who have lived under communism’s evils.

Both writers have the profile that is now chic in literary circles: they represent immigrant cultures; they are alienated; they have no connection through religion with traditional Western culture; and are very interested in the specific challenges of living with same-sex attraction.

The last is a kind of de rigueur bona fide for seriousness now, not exempting Disney productions, which used to be innocent of such distractions. The trope makes for one of those Russian nesting doll effects: an alienation within an alienation within an alienation.

Alienation is the name of the game in our culture, generally, and helps explain why anxiety and anger is overwhelming us. The traumas of immigrants can mirror America’s conflict with the very idea of America. We see people desperate to be part of a society that is shattered into so many rivaling subcultures. In a Darwinian culture contest, the fittest do not always survive, and as a result, the lowest common denominator for culture might take us back to the Stone Age. The loss of values belonging to historic cultures matches the absence of the same in our culture.

There was a character in an old Broadway show who had a cracked pocket makeup mirror in her purse. When asked why she used such a thing, she said that it made her look like she felt. That is a little like what I feel about reading the two novels and looking at the news these days of the desperation at the border. We don’t look so well put together. Maybe that’s a message we can meditate on.