Even though I attended a college seminary named for him, I did not know a great deal about St. Charles Borromeo. I have learned much more recently thanks to a book “Charles Borromeo: Selected Orations, Homilies and Writings,” (Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2017) which has selected writings of the saint.

I consulted the book recently because of the coronavirus (COVID-19) trauma that is affecting the whole world. St. Charles was the archbishop of Milan when the plague hit the city in 1576. Many of the issues he and his people faced sound familiar to us because of recent events.

The saint did not suspend Masses but did suggest they be celebrated outdoors, especially at crossroads where people could attend in a kind of rough “social distancing” protocol. That reminds me of the reports of drive-through confessions in parishes around the country amid our present crisis.

The saint was concerned about the body and souls of his faithful. He spoke about the quarantining that went on with those afflicted, who were sent out of the city because they were infected, “pushed out of their sweet familiar homes, sick and only half-alive, with all their goods left behind; and finally led on deathly, sordid carts to those enclosed areas which are much more like stables than civilized dwellings, and from which there is little or no hope of returning.”

The news says Singapore and the Republic of Taiwan have special quarantine hospitals, and I trust they are better than Milan’s “stables.”

St. Charles saw the spiritual needs of such people and worried about those deprived of the sacraments as they faced death. Although Milan had an abundance of priests, there were problems with attending to the dying. If parish priests attended those with the plague, such pastors were “turned away by their parishioners, if they have already ministered to the afflicted, until the passage of time can show that they themselves are healthy.”

Because the quarantine sections were far from some parishes, the archbishop sent priests to the people there. “I have sought outside priests, and not in vain, but we need still more,” he explained in a sermon he preached to religious superiors of monasteries and congregations. “I do not find other priests willing to help, and I cannot force them, nor should I.” So he asked for religious priests to volunteer: “if there is anyone whom we could expect to come and save others and imitate the Lord in this way, it would be you first of all.”

St. Charles admitted the danger involved in the work of exposing oneself to the deadly disease. He notes, however, “Alas, we see daily many who undertake these same dangers, led on by the hope of some utterly meager reward, which indeed they do not obtain.” It makes me think of what he would say of those who risk the crowds at Walmart to engage in hoarding what they don’t need.

If the priest did not escape the deadly sickness, St. Charles said, “It will be a quicker attainment of blessed glory.” Besides, he pointed out, many who tried to avoid the disease at all costs had nevertheless contracted it. The saintly archbishop reminded the religious superiors that Pope Gregory XIII (to whom the world owes the Gregorian calendar) had mandated attention to the sick of the plague.

St. Pope Paul VI once referred to his predecessor in the Archdiocese of Milan as “a practical genius.” St. Charles’ appeal to the religious superiors demonstrates a patient development of an appeal that would be very hard to refuse. His ending was a great example of persuasion:

“But if someone does contract the disease, and others are no longer there [for the work], then I myself, who will be going out among you every day, on account of the sick, will be there. I shall be charged with caring for your health in both body and soul. I will willingly come to your aid. I offer myself to you right now as a minister of the Sacraments, if that should be necessary.”

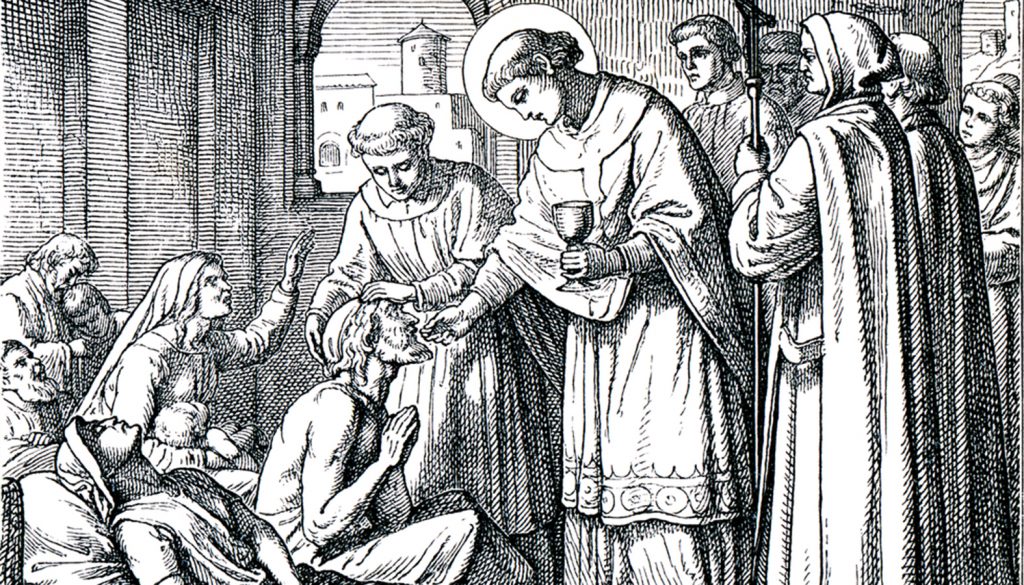

The saint was as good as his word in this regard. There are stories of his reaching over the corpses of others to give Extreme Unction (as it was called in those days) to those so close to death that they had already been thrown among the dead. Many great works of art depict the saint in the midst of the plague crisis. Some of them (including a small carved wooden statue that is in my rectory chapel) depict St. Charles processing through Milan, asking for God to spare the city. He put a noose around his neck to indicate he offered his own life for that of his flock, a dramatic and quite disturbing symbol.

After the plague was no longer threatening the city, St. Charles wrote an address that included reminders for Christian living, with brief admonitions exhorting reform of life to those whose lives had been spared.

One of his points was that the experience of the plague should strengthen faith. That is something I see sorely lacking in popular responses to the crisis. There is a constant stream of lame jokes, purported cures, conspiracy theories, political jousting, and more hand-wringing than hand-washing, it seems.

Just recently, someone sent me a weird video “thanking” the virus for reminding us of our common humanity. It may be that the crisis provokes some fellow-feeling, but what I don’t like is the completely secular point of view on evidence. We are grateful because there is less pollution in the air, because our lives in quarantine are less hectic, because some people are moved to small acts of generosity, giving from their excess, etc. Where’s the faith element in such mental exercises?

Reading about St. Charles has also been an antidote to some of the hysteria. He made clear that what is important is what touches on eternal life. He was not afraid to mention God amid the terrible situation, reminding the people who had lived with the terrible scare of disease to “flee bad company more that you would flee the plague.”

Some photos of people’s exaggerated precautions about the coronavirus have circulated, like people walking into grocery stores in bubble wrap, etc. I think the best words of caution in or out of whatever crisis “du jour” we find ourselves in, as St. Charles said, is to “always have God before your eyes, in whose sight you stand and who always sees you.”