A couple of weeks ago, on a Thursday, I took a field trip to Mount Wilson, the 5,710-foot peak northeast of L.A.

You need a five-buck adventure pass to park at the observatory, so I picked one up at the Shell station just off the 210, then drove 20 miles from La Cañada on the picturesque Angeles Crest Highway.

On the way I listened to Bach trios and admired the clumps of butter-yellow Scotch broom. Then I turned off on Mount Wilson Road and drove another five winding, increasingly beautiful miles. A vista of violet mountains and deep green gorges opened round one bend. I pulled off and, having brought my breviary, said a Morning Prayer with the sage and the squirrels.

With its dirt roads, pickup trucks, scattered buildings and masses of white domes with spider-like supports, the feel at the top of Mount Wilson is of a grown-up Boy Scout base camp for astronomy enthusiasts with very wealthy parents.

In fact, the observatory was founded in 1904 by George Ellery Hale, a graduate of Harvard and MIT, and a pioneer in the “new astronomy” of astrophysics. Supplies were brought nine miles up the mountain, often by mule, on a narrow dirt trail.

Hale encouraged such early-20th-century astronomy greats as Harlow Shapley and Edwin Hubble. With their sharp scientific minds and state-of-the-art telescopes, they made the discovery that the universe is expanding. They postulated the Big Bang theory. Mount Wilson became world-famous.

Today, there are birdhouses and stands of lupine and groves of wild oaks. You can walk the adjacent Rim Trail if you like.

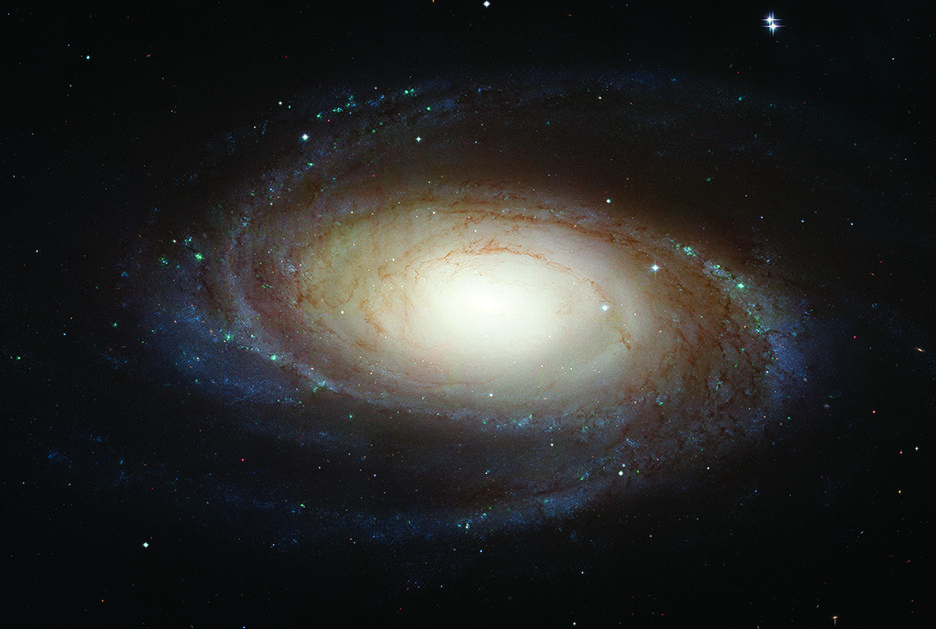

In the Astronomical Museum, thrilling photos of sunspots, blood-red hydrogen clouds, and spiral nebulae are on display.

Other attractions include the Snow solar telescope, the 60-foot solar tower, the 150-foot solar tower, the 60-inch telescope and the CHARA exhibit hall.

I went right for the 100-inch Hooker telescope, housed in a building with a huge white dome. Outside, I read of the unlikely pairing of Edwin Hubble, a Rhodes scholar, and Milton Humason, who had almost no formal education and had started out at Mount Wilson as a janitor.

Humason did the painstaking photography that helped Hubble measure the distances and redshifts of several dozen spiral galaxies, including the Andromeda.

The farther the galaxy, they discovered, the faster it seemed to be receding from us — a phenomenon familiar to all who have ever known unrequited love.

I had the place to myself. Up three flights of a narrow steep stairway, I came upon a darkened deck that gave on to a kind of hushed, spot-lit temple. Behind what looked like a bulletproof layer of convex glass, the giant telescope — the largest in the world from its completion in 1917 to 1948 — was suspended above a stage.

I pressed a button and jumped as the voice of Hugh Downs boomed from hidden speakers. “The main mirror weighs 4 1/2 tons,” Downs reported. “Its surface is ground to a precise shape accurate to within a few millionths of an inch.”

There above the stage, on an elevated platform, he continued, was the “somewhat rickety wooden chair on which the famous American astronomer Edwin Hubble sat while he guided the huge telescope in his work. It was from this place that humankind, through Hubble’s achievements, first discovered how big the universe is. … Hubble … was the first to prove that our galaxy [the Milky Way] is an undistinguished member of a vast population of billions of galaxies extending throughout the heavens as far as we can see.”

The voice continued: “Hubble’s discoveries were the last great step in the Copernican revolution of thought concerning man’s place in the cosmos. … Hubble showed that our galaxy is not the center of the universe. There is no center.”

There is no center. The words rang in my ears. Maybe not. But what if this infinitesimal point — in real time and real space — where Jesus Christ became man and pitched his tent among us, really is the center?

“If life exists elsewhere in the universe, it’s likely to be far older and possibly far more advanced and more intelligent than life on the Earth.” Maybe. But what if the very highest form of intelligence consists in learning to love one another as Christ loved us?

I glanced at my watch and thought, “Is a galaxy more of a wonder, or a mystery, than a human wrist? Can even the most finely calibrated telescope explain the human urge to worship?”

Outside again, I looked up at the clouds and thought of Emily Dickinson, a woman who rarely left her house but — like Hale — had closely pondered the heavens.

In the late 1800’s she had written:

The Brain — is wider than the Sky —For — put them side by side —The one the other will containWith ease — and You — beside —

The Brain is deeper than the sea —For — hold them — Blue to Blue —The one the other will absorb —As Sponges — Buckets — do —

The Brain is just the weight of God —For — Heft them — Pound for Pound —And they will differ — if they do —As Syllable from Sound —