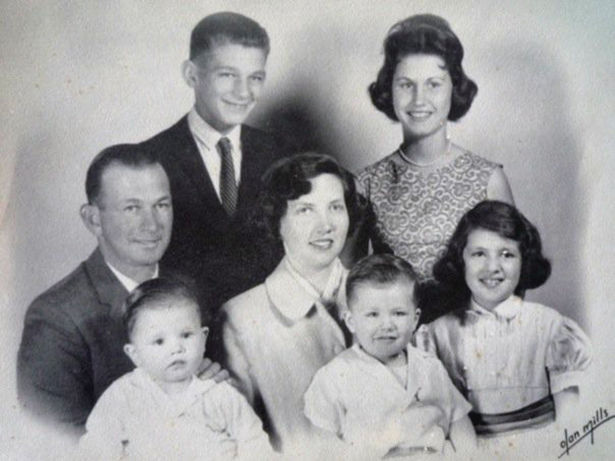

My father was so obsessively modest that it was a standing family joke that the only parts of his body my five brothers, two sisters and I had ever seen were his hands, neck and face. He kept the rest swathed, even in the midst of a New England heat wave, in a long-sleeved chambray work shirt, Sears jeans and a pair of construction boots. For our bricklayer father to have walked around in shorts or sandals or even a T-shirt would have been tantamount to a regular father parading around the house in a jockstrap.

Dad’s approach to child-rearing was to deprive himself of every luxury and, when it came to us, act like he’d just won the lottery. No blunder was so great my father couldn’t overlook it, no lapse in common sense so moronic he wouldn’t ignore it, no mistake in judgment so insanely misguided that he wrote us off for good.

The older I got, the more I wanted to know his inner thoughts, his secret sorrows, his regrets. I wanted to know him the way he knew me — and then I’d realize that I had never even seen his bare arms.

My then-husband Tim and I moved to Los Angeles in 1990. On the afternoon of Christmas in 1995, my sister Jeanne called from back East. They’d rushed dad to the hospital after dinner. He was in intensive care with congestive heart failure and deteriorating kidneys, and it looked like he might not make it.

We flew to Boston the next morning and, an hour north of the airport, pulled into the driveway of our rural New Hampshire homestead.

Over bowls of mom’s lobster stew, Jeanne delivered the latest medical update: dad was on intake and output, he was taking oxygen and he couldn’t void on his own, she informed us.

It felt almost sacrilegious to be discussing my father’s intimate bodily functions, but that was nothing compared to the bombshell my little sister Meredith dropped next.

“I saw his leg today,” she announced reverently.

“All of it?” Ross ventured.

“No, just the left shin. The blanket fell back for a second and, between this little brown sock he had on and his johnny, I actually saw part of his leg.”

“What did it look like?” I breathed.

“White. Really, really white. And waxy. And totally hairless.”

We digested this news in silence. A massive wall was crumbling. Nothing could illustrate the critical nature of the situation more clearly than the fact that, after 76 years, my father had let one of us see part of his body without dying of shame.

The next morning, Ross, Tim and I got up early and headed for the hospital.

We filed in past a silver aluminum tree, buzzed the ICU desk and then we were crowding into his room and there he was, lying in bed with the blanket pulled up to his chin. Tubes sprouted from one wrist and his face was gaunt. Still, he looked happy in a dazed sort of way, drinking us in with his faded hazel eyes.

“How’re you feeling, Al?” Tim asked.

“A little tired,” he admitted. A little tired?! He was practically dead! “But Jeez, isn’t this a treat,” he continued. “Can’t remember the last time I got so much attention.”

“So what’s wrong, anyway?” I asked, leaning over to kiss him. “Have you talked to the doctor?”

“Who knows?” he replied, dismissing the whole bothersome subject with a wave of his frail hand. “Kidneys are fouled up or something.”

“Time to check for blood clots,” the nurse announced cheerfully, wheeling in a refrigerator-sized machine and slathering green gel on my father’s right leg and running a computer cable up and down his calf.

“It’s showing up on that camera monitor,” Dad said, gesturing to a grainy image in black and white by the bed, and then — unbelievably — he said, “Go on, take a look.”

I approached gingerly, straining out of the corner of my eye to get a look at the real leg, exposed at last after all those swaddled years.

My heart turned over at the sight of it, bent at the knee and veined with pale blue, laid out on the white sheet like a cut of baby lamb. There was something holy about it, that flesh enfleshed again in my brothers and sisters and me.

I thought of those reliquaries in Italian churches: tiny glass caskets housing fragments of saints — a fingernail paring, an eyelash, a swatch of a bloody shirt. I felt the vulnerability of a God who came into the world as a baby: poverty-stricken, helpless, exiled.

The memory of that day in the hospital floated back to L.A. alongside our 747, hovered in my mind’s eye and assimilated itself into my bones and blood.

It is hidden away again now, shrouded in the mystery of love made incarnate: in eyes that will one day go blind, hands that will falter, hearts that will stop — and, in stopping, will pass life on.

It is in that place within my deepest core where it is Christmas all the time.

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books.