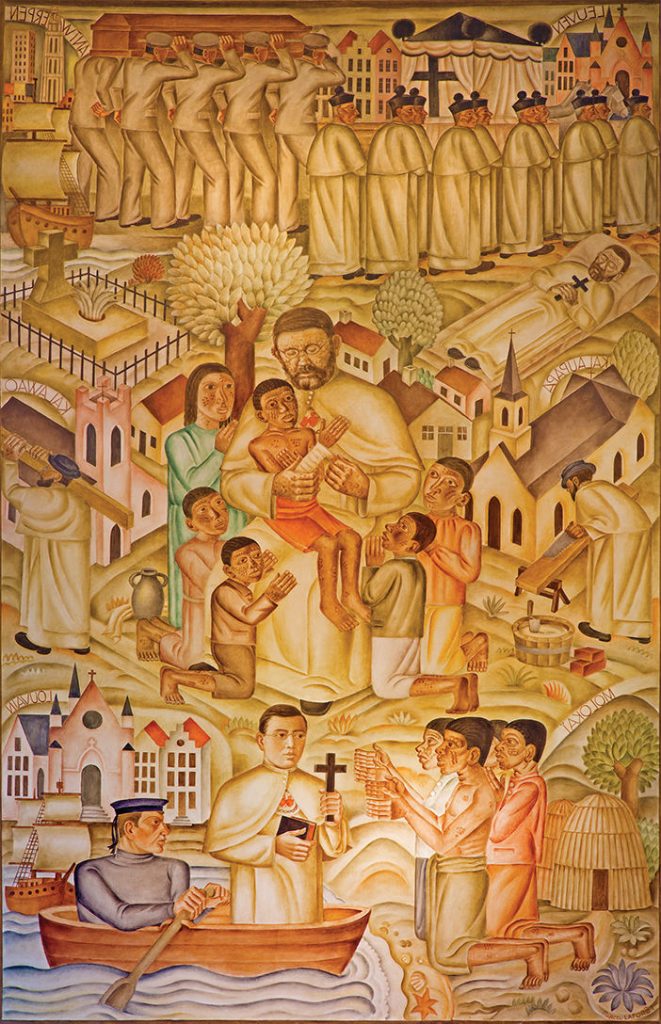

May 10 is the feast day of St. Damien (1840-1889). As a young priest, Father Damien made his life among the lepers at the colony of the Hawaiian island of Molokai — then contracted, and died of, leprosy himself.

He was canonized in 2009, and is also the unofficial patron of those suffering from HIV and AIDS.

“Not without fear and loathing,” Pope Benedict observed, “Father Damien made the choice to go on the island of Molokai in the service of lepers who were there, abandoned by all. So he exposed himself to the disease of which they suffered. With them he felt at home. The servant of the Word became a suffering servant, leper with the lepers, during the last four years of his life.”

Then and now, disfiguring diseases makes us uncomfortable. They bring us face to face with our mutilated hearts. They reveal to us how very little we are willing to suffer ourselves.

Books and films about those with Hansen’s Disease, as leprosy is now known, abound.

Neil White, for example, was a high-rolling Louisiana magazine publisher who kited one too many checks. Starting in 1993, he served 18 months for bank fraud in federal prison in rural Louisiana.

But this was no ordinary prison, as the jacket of “In The Sanctuary of Outcasts” —the book White wrote about his time there — points out.

“The beautiful, isolated colony in Carville, Louisiana, was also home to the last people in the continental United States disfigured by leprosy. Hidden away for decades, this small circle of outcasts had forged a tenacious, clandestine community, a fortress to repel the cruelty of the outside world. It is here, in a place rich with history … amid an unlikely mix of leprosy patients, nuns and criminals, that White’s strange and compelling journey begins.” White’s book is a highly entertaining mix of the history of Carville, personal memoir and spiritual awakening.

For decades, members of an order of Catholic nuns called the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul faithfully treated the patients at Carville. A PBS documentary, “Triumph at Carville: A Tale of Leprosy in America” (2002), tells more of the story.

Finally, “The House is Black” is an astonishing 1962 documentary short by the iconoclastic Iranian poet, journalist and filmmaker Forough Farrokhzad (1935-1967). In it, she captures the lives, suffering, beauty and humanity of the members of the Behkadeh Raji leper colony in Iran.

Shot in grainy black and white, and accompanied by a haunting score, the film begins:

There is no shortness of ugliness in the worldIf man closed his eyes to it,there would be even more ...On this screen will appear an image of ugliness …a vison of pain no caring human being should ignore.

In voiceover, we hear snatches of the Koran, Farrokhzad’s own poetry and the Psalms:

I will sing your name, O Lord.I will sing your name with the 10-string lute.For I have been made in a strange and frightening shape …Who is this in hell?Who is this in hell,praising you, O Lord? ...

During the shooting of the film, Farrokhzad bonded with the child of two lepers, a boy named Hossein Mansouri. She adopted the child, brought him to live at her mother’s house and, having swerved her Jeep to avoid hitting a school bus, died in a car crash at the age of 32.

But we needn’t travel to Molokai or Carville or Iran to meet the leper in others and the leper in ourselves.

We need only, say, walk to morning Mass at St. Francis of Assisi Church in Silver Lake, as I did recently.

“All over the world,” I wrote of my experience, “all day, every day, people are suffering, and here comes Barry, the homeless schizophrenic and hopeless alcoholic who wanders up and down Sunset Boulevard, one grimy hand clutching a plastic bag holding his worldly belongings, the other held out in a perpetual plea for booze money. What to do in the face of such suffering? What to do with your brokenness, your feebleness, your weakness, your own suffering and doubt and loneliness and fear? You give Barry a couple of bucks. You make sure to shake his hand and thank him, because that is Christ. And you keep walking —to Mass.”

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t shake Barry’s hand out of some conscious decision to kiss the leper and certainly not out of virtue. To live alone, work alone and mostly worship alone is to be a kind of leper myself. I shake Barry’s hand because I desperately need a human being to touch me.

St. Damien was a prickly personality with many shortcomings. So am I.

I’m so poor I long to shake Barry’s hand. I’m so poor I need Christ.