Imagine this scene in a small cantina in a part of Guatemala rarely visited by tourists: A man is drunk and is getting loud. He is weeping and cursing his father for something that happened more than 30 years before. A mystery was solved in his drunken lament — a piece in a puzzle that had been missing was found.

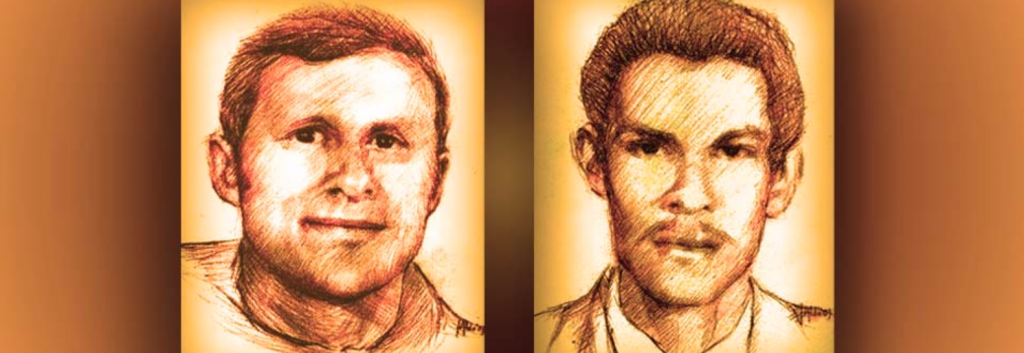

He had been the unwilling accomplice of the murder of a Franciscan missionary priest, Father Tullio Maruzzo and his driver, assistant and factotum, Luis Obdulio Arroyo. They were assassinated on the evening of July 1 in 1982, near the Mayan ruins of Quirigua, a site made famous by hieroglyphics that predicted the end of the world (portrayed in the movie “2012”). The priest was coming back after celebrating Mass for a Cursillo retreat.

The day before, some men involved in one of the paramilitary groups formed in the bitter civil war in Guatemala threatened him and pushed him around. He had told them, “I have no use for violence, only for the love of Christ; that is my duty.”

The day of his death, he had participated in the pastoral visit of the bishop of the Apostolic Vicariate of Izabal. Typically, the friar had committed himself to the Mass with the cursillistas, even after a long day’s work. He and his helper had made a Cursillo a few months before, and he was sold on the movement.

At 10 p.m., they were passing the ruins of Quirigua, when a young boy stopped them asking for a ride. Their usual practice was not to pick up anyone — there had been too many threats and attempts on the priest’s life, including a grenade attack at his former parish house. But a child was exceptional, and the priest decided to help.

As soon as they stopped, armed men jumped out of the bushes. They beat the priest and Obdulio, and then shot them dead. That was why the boy — now a man — was cursing his father. He had been the bait for the deadly trap.

If war is hell, as General William Sherman said, civil war must be the deepest circle of damnation, because it is fratricide.

Guatemala suffered war for three decades. It was part of what Archbishop Arturo Rivera y Damas of San Salvador, one of the forgotten heroes of the Church in Central America, described as the Cold War gone hot. The systemic injustice and the lack of development of the countries in Central America made them the proxies of geopolitical tensions and ambitions far beyond their borders.

Father Tullio and his twin brother Lucio were from the Veneto region in Italy; their parents were poor farmers. Father Tullio and his brother had received ordination to the priesthood by Cardinal Guiseppe Roncalli, the patriarch of Venice and future St. Pope John XXIII.

Lucio was sent to Guatemala days after his ordination; his brother had to wait seven years before he was sent in mission. Father Tullio was first assigned to Puerto Barrios, on the Atlantic coast, and helped in the construction of what is now the cathedral of the Vicariate of Izabal.

A few years later, he was sent to attend pastorally to the poor workers on the banana plantations run by the United Fruit Company. He was the first pastor of San Jose Parish in Morales.

The conditions of the people were miserable, malaria was rife and the region was a nursery for the guerrilla insurgency in Guatemala, a conflict much more bloody and destructive than those of other countries in Central America, but hardly known in the U.S.

Father Tullio was not a great orator; he was reserved and peaceful, but he did an incredible amount of arduous work, traveling by foot and horseback to 72 different villages to celebrate the sacraments and give formation to the lay leaders in the communities. This made him suspect with the counter-insurgency, which viewed any leadership in the rural areas with alarm.

One year before he was killed, Father Tullio had written to his relatives in Italy, “The Church has to be with the poor. They need justice and understanding.”

His superiors moved him from Morales to Quirigua after grenades were thrown at his rectory and his pastoral formation center. In Quirigua, he met Luis Obdulio Arroyo, who drove for the friars and did many different tasks.

Luis Obdulio was warned away from his work with the priests, but he said, “I would rather die working for a priest than be found dead of drink in a cantina.” The rough and honest eloquence of the new blessed should make us all love him. To serve God gave his life meaning, a meaning that speaks volumes to us about justice and peace for the poor.

Father Tullio and Luis Obdulio will be beatified on Oct. 27 in a ceremony in Guatemala. Both these new blesseds were martyrs of pastoral charity. The phrase figures in the documents of the Second Vatican Council, and means the love that incarnates Christ’s shepherding the faithful.

There are people who confuse this charity with ideological positions, but the hard but simple life of these two workers in the vineyard should be a clear example.

In troubled times, when the Church stood with the people, pastoral workers suffered and even lost their lives because of their imitation of the Good Shepherd who gave his life for the flock. In such a time of confusion and persecution, a simple gesture like stopping on a road at night to help a child could be fatal.

In the same month Father Tullio and Luis Obdulio died, Father Stanley Rother, a missionary priest from what was then the Diocese of Oklahoma City and Tulsa, and the first U.S. citizen beatified as a martyr, was killed.

His beatification last year, and that of the martyrs of Quirigua this year, should throw a light on the witness of the Church in Guatemala for us in the United States, and inspire us all.

Father Richard Antall is a Cleveland priest. He was a missionary in El Salvador for 20 years and served as moderator of the curia for the Archdiocese of San Salvador. He is the author of “Witnesses to Calvary: Reflections on the Seven Last Words of Jesus” (Our Sunday Visitor, $13).

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.