A sermon — not the classroom — was my introduction to Flannery O’Connor.

My priest praised the wisdom of her story, “Revelation”: how the ending forces us to question our complacent, assured sense of faith. I then read all of her work that I could find, and like many young Catholic writers, saw her as a template for writing and thinking as a Catholic.

Here was a profoundly, publicly Catholic writer who was published in the finest secular magazines, and revered for her storytelling talent.

Few scholars have considered O’Connor’s talent and life with as much depth and breadth as Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, a Fordham University professor who has written critical examinations of O’Connor’s work and life, and has even channeled the classic story writer’s voice in poems.

O’Donnell’s appreciation for O’Connor makes her the perfect critic to write a necessary, complex book about O’Connor’s views on race.

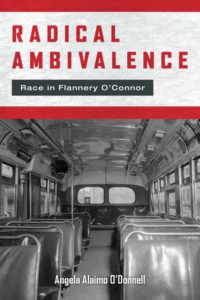

“Radical Ambivalence: Race in Flannery O’Connor” (Fordham University Press, $30) is a significant, challenging work of criticism. Not challenging because it is esoteric — O’Donnell’s prose is clear and precise; challenging because O’Connor has been canonized by many as the prototypical American Catholic writer. For good reason: Her fiction is strange, unique, perceptive, and God-haunted.

Yet O’Donnell’s book arrives with some uncomfortable, but important, revelations.

As O’Donnell notes, critics have considered O’Connor’s views on race since the 1970s, but O’Donnell has been given permission to reproduce previously unpublished letters from the writer.

In this unearthed correspondence, O’Donnell notes, “O’Connor demonstrates attitudes that are hard to describe as anything but patently racist.” Perhaps even more concerning — from an archival perspective — is that racist language was scrubbed from O’Connor’s collected letters. Phrases and sentences were omitted, without ellipses or notation.

Angela Alaimo O'Donnell. (AngelaAlaimoODonnell.com)

This is noteworthy. A writer known for her frank, sometimes violent fiction — stories that shock our senses to reveal the presence of God among us — has been sanitized. On one hand, this shouldn’t come as a surprise. O’Connor was the first to admit that she was a sinner in need of grace. Yet that is no excuse for racist language, even in private correspondence.

O’Donnell begins with O’Connor’s first published story, “The Geranium,” about an old white southerner who moves to New York City to live with his daughter — but feels terribly out of place. After a tense encounter with a black neighbor, O’Donnell notes that the main character “grieves for himself and for the loss of the Jim Crow life he has led and loved, the comfortable dispensation of white privilege and black submission.”

That was 1947. In 1964, O’Connor was still reworking the story, and published a new version as “Judgement Day.” In that later version, O’Donnell explains, O’Connor imbues more complexity and nuance. She “explores more fully and deeply the investment of white culture in a racist dispensation.”

The main character, Tanner, “does not know how to live in the world he encounters, one in which his very identity is threatened and rendered uncertain.” Although white people like Tanner “stand to gain the most from the system” of racism, they also “suffer from it in ways they are unaware of, and rooted within the system are the seeds of its destruction.”

This is a theological, and spiritual, concern. Here O’Donnell cites the work of black Catholic scholars like M. Shawn Copeland and Father Bryan N. Massingale.

One particular quote from Copeland is essential: “Racism spoils the spirit and insults the holy; it is idolatry. Racism coerces religion’s transcendent orientation to surrender the absolute to what is finite, empirical and arbitrary, and contradicts the very nature of religion.”

O’Donnell reminds us that despite O’Connor’s Catholic belief that all belong to the mystical body of Christ, in her own parish, O’Connor “would never receive the Eucharist with an African American. The Church she belonged to was, effectively, a white church.”

Sadly, O’Connor was so good at “portraying the evil human beings are capable of, and one of the reasons she was able to see it so clearly in her fellow creatures is that she was subject to it, as well.”

This is actually a very Catholic vision of literature and art: Artists are usually not saints. It is in the moral drama of their art that we might find some transcendence and wisdom.

O’Donnell has praise for O’Connor on this point: “It is her white characters who are put on trial and, nearly always, found wanting. In fact, whiteness itself is put on trial in O’Connor’s fiction, with all of its accompanying pride and prejudices, ugly superiority, and self-righteous evildoing.”

This observation is not made to excuse O’Connor’s problematic statements and stances in her letters. O’Donnell wants us to recognize that O’Connor was very much a product of her time and place, and to realize that such recognition is not sufficient reason to explain away her bigoted views.

“We typically assume,” O’Donnell writes, “that private expressions in O’Connor’s letters would tell us more about what and how she thinks than the public art of her stories, but given the nature of the two kinds of discourse, fiction seems more reliable” than her letters.

O’Donnell’s conclusion is wise: “In the end, there is no need to choose one Flannery O’Connor over the other, for the two forms of discourse are expressions of her mind and heart, and in order to fully appreciate her humanity and her art, we need both.”

O’Donnell’s book is not a polemic. We don’t leave her treatment with the conclusion that O’Connor should no longer be read, studied, or valued. Rather, she patiently and thoroughly demonstrates how an honest look at O’Connor and race reveals a more authentic understanding of how racism stains a Christ-centered vision of the world.