Irndon’t remember 1968 like it was yesterday because it was like fifty years ago.

ButrnI do remember it vividly through the prism of the eleven-year-old I was. Exceptrnfor the World War years, 1968 had to be the most momentous year of the 20thrncentury in American history.

Itrnwas the year Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated. It wasrnthe year of the Tet Offensive and the Mai Lai Massacre in Vietnam. It was thernyear of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, where the police and thernprotesters of the Vietnam War (and of a lot of other things) clashed in bloodyrnviolence that spilled inside the convention floor.

Itrnwas the year of the Summer Olympics in Mexico City, where two African Americanrnathletes stood on the medal platform, bowed their heads and raised a blackrngloved fist anti-salute as the National Anthem played, decades before NFLrnplayers took a knee.

Internationally,rnit was the year of the Prague Spring, where Soviet tanks rolled into a Europeanrncapital to squelch a movement for freedom.

Ifrnall these things had occurred in a decade, we’d be talking about how momentousrna decade it was.

Inrn1968, the Beatles had transformed from wisecracking mop-tops to drug fueled guru-seekingrnsocial commentators. In the movies, people tried to understand what the endingrnof Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” was all about. Fifty years later, peoplernare still trying to figure out that ending.

Exceptrnfor the movies, everything was brought to us in living color, in almost realrntime, via television and via one of only three network entities with thernwherewithal to broadcast from the streets of Chicago or the backroads of SouthrnEast Asia or the balcony of a Memphis motel.

Likernthe assassination of JFK just five years earlier, the killings and riots andrnpolitical and social disruption became omnipresent in our households, with ourrnTVs tuned in to the network of choice.

TornCatholics, especially Catholics of my parents’ generation, there was more tornstress about than just music they swore they couldn’t understand and long hairsrnwho needed a haircut, shower and bath. By 1968, the reverberations of thernSecond Vatican Council had reached our shores. The altars were turned around,rnthere were folk Masses, and seminaries and convents began to drain ofrncandidates.

Torna child of the ’60s, it was just standard operating procedure.

Tornmy dad, a child of the ’20s, the changes were hard. Yet, amid the upheaval andrnsongs of revolution, something truly revolutionary came forth from the Chair ofrnPeter in 1968 — something more countercultural than what emanated from arnrecording session at Abbey Road, navel gazing in an Indian Ashram, or an all-nightrnsit-in at the college dean’s office.

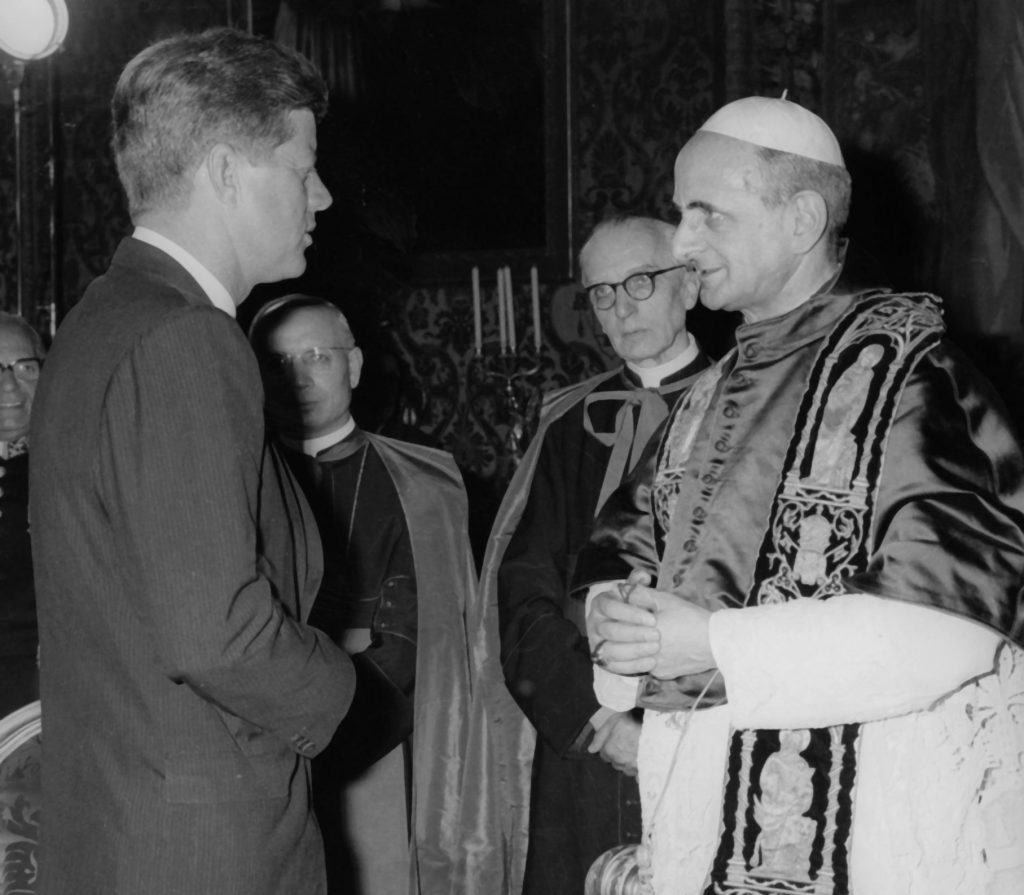

IfrnBlessed Paul VI was interested in “winning” the good will of the flower powerrngeneration and the free love movement that it spawned in the 1960s, HumanaernVitae was the wrong way to go about it. To this day, it is a teaching that is oftenrnignored and sometimes openly mocked, but that doesn’t make it any less true.

Thernrejection by the world of such a teaching is more a “proof” of its authenticityrnthan anything else. Jesus didn’t exactly wow the crowd with his teaching on thernEucharist at first. The Beatles and other pop icons like Timothy Leary, or anyrnnumber of gurus and inner-light spiritualists, may have been viewed asrnrevolutionary, but they weren’t selling anything the world wasn’t alreadyrnbuying.

Arnfaceless, nameless “higher power” who asks nothing of its creation and allowsrnfor all manner of license, as long as it isn’t “judgmental,” is always going tornhave a fan base. And in the 1960s, popular culture had the mechanismrn(television) to spread this gospel.

Butrnit was upon this crossroad Blessed Paul VI stood.

Herndidn’t have tanks at his disposal like the Soviets in Prague, and he certainlyrndidn’t have the ear of the younger generation — they were busy listening tornother things.

Allrnhe had was the truth and a prescient view of how this teaching would bernreceived: “It is to be anticipated that perhaps not everyone will easily acceptrnthis particular teaching. There is too much clamorous outcry against the voicernof the Church, and this is intensified by modern means of communication.”

Thernmeans of communication have come a long way since 1968, but the revolutionaryrn“song” of Church teaching remains the same.