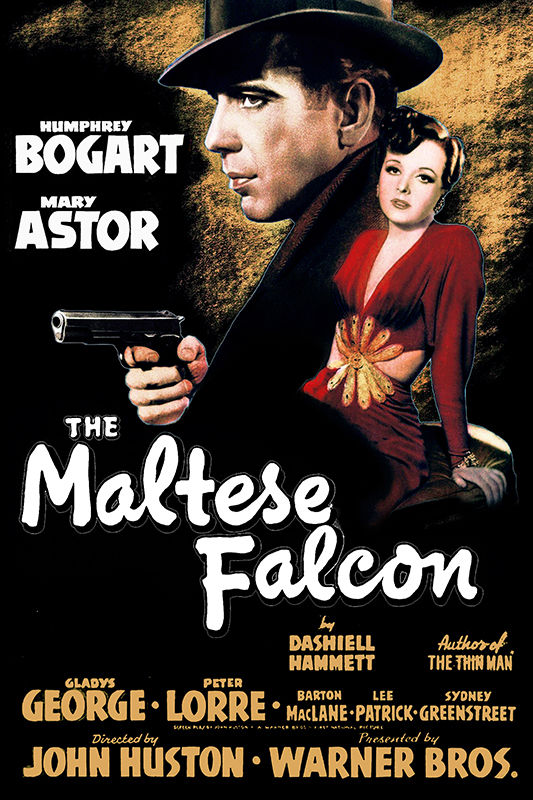

It’s the 75th anniversary of the release of the film noir classic film “The Maltese Falcon” and a friend of mine sent me an article/retrospective about this movie that got me thinking. The critique brought up a point about not only the film, but the main literary thrust of the story’s creator Dashiel Hammet that I had heretofore not fully realized.

The critical Rosetta Stone the article deciphered in both Hammet’s novel and in the film adaptation, directed to near perfection by the great John Huston, was that none of the characters change. Obviously their circumstances change dramatically. People are murdered, a treasure is thought found, but remains lost and at the end of it all, somebody has got to go to prison.

Cutting through all the tangled webs of deceit is Sam Spade, played likewise to near perfection by Humphrey Bogart, who comes out at the end of the film unscathed. From the first frame on he remains the same outside-the-lines character with his own code of ethics and singular impulse to look out only for number one. The femme fatale played by Mary Astor may have a big change in her circumstances coming her way — namely prison — but at the end of the film she too remains the same duplicitous lower order creature she was when we first laid eyes on her.

The fantastic character actor Sidney Greenstreet as the rotund “Guttmann” may not have found his “bird,” but he is as intent as ever at the end of the film to continue on the quest. All the other minor and major characters making up this menagerie likewise stay on their own personal paths despite circumstances that have diminished their prospects.

There is no road to Damascus moment in this film, which, when you think about it, does not make it unique compared to other works of art at various elevations above and below the classic American detective novel.

Do any of the characters in Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” actually change? Sure the leads fall in love, but Romeo was in love before he even met Juliet and Juliet falls instantly for Romeo. Tybalt is always aggressive and combative until his death and Mercutio is obsessed with great one-liners even to the point of his last breath.

It is precisely because each of Shakespeare’s characters stay true to their own selves that so many bad things start to happen. And like some kind of dramatic alchemy, the chemical equations of each character’s ingrained traits combine and combust in a concoction of tragic consequences.

Movies and stories where protagonists do experience some profound metamorphosis and where that change is pulled off with artistic believability, are harder to find than the “Maltese Falcon.” Usually so-called “family” entertainment and Hallmark Channel Christmas time TV movies contain these 180-degree turns in their protagonists and antagonists alike, and, as a whole, this faire is rather unappealing. Dickens pulled it off to great effect in “A Christmas Carol,” but he also tempered the transformation of Scrooge by couching him in a fantasy.

There is one source where we find this kind of transformation and it is never unappealing or without profound impact — Scripture. It’s the radical message of the New Testament: we MUST change. Simon must become Peter and transform from an impetuous and weak willed fisherman to a shepherd of the Church and fisher of men. Saul must turn away from persecution to willingly become a martyr himself. Thomas must stop doubting, believe and set out on a far flung sojourn.

Granted, some saints don’t change; they seem born with an inner compass that points toward God. Many more though do go through radical change, whether they turn their backs on hedonistic ways as St. Augustine did, or reject a life of privilege and riches like St. Francis of Assisi.

Characters in movies and television and literature of the past, present and probably future who exhibit this kind of transformation are rarely portrayed well when they are portrayed sympathetically. (You usually wind up with some Christian-themed feel-good movie that is marketed to Christian churches.) Most times this kind of change is used as a source of ridicule or scorn. Holier than thou types are almost always exposed as hypocrites with skeletons and other friends in their closets.

It is the Sam Spades of the world that the world holds up in envy. But Sam Spade never changes or deviates from his self-imposed moral universe. He is a god unto himself, like the rich man in Scripture who asked Jesus how to get to heaven and went his not-so-merry way after hearing an answer not to his liking. The real rebel is not the hardboiled detective who seems to live outside of society’s norms — it is the man or woman who falls to their knee in weakness and calls on God for forgiveness and rebirth. Maybe due to our fallen natures, portraying that kind of real heroism is so much quicksilver in the hands of creative types.

But, as the saying goes, Jesus loves us just where He finds us, even Sam Spade — only He loves us so much He doesn’t want to leave us there. To reach out and take hold of the hand God extends our way is the greatest character arc we could ever hope to traverse.

Robert Brennan has been a professional writer for more than 30 years, including many years in the television industry.