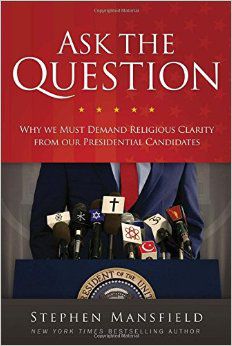

Religion comes up a lot in politics, and yet, not at all. Not substantively. That’s the argument author Stephen Mansfield makes in Ask the Question: Why We Must Demand Religious Clarity from Our Presidential Candidates.

Kathryn Jean Lopez: How do “we distance ourselves from the vital world of politics and government” by not knowing deep things about a candidate’s religious faith?

Stephen Mansfield: If we don’t “ask the question,” if we don’t devote ourselves to understanding what we can about candidates—their religions in particular—before they enter office, then we turn elections into high-stakes gambling events. We won’t know how religion will determine executive action and so we will vote like casino addicts blowing on dice and hoping for a windfall. Knowledge and integrity will be thrust aside. Votes will be cast for reasons other than a candidate’s likely performance in office. Once removed from the realities of the campaign, we will be equally removed from the realities of the office and thus of our country.

Lopez: You describe JFK’s election as a dividing line in the history of religion and politics in America. How deep was his impact in privatizing religion?

Mansfield: Kennedy addressed concerns about his Catholicism by driving a rhetorical wedge between personal faith and public policy. He had sworn allegiance to the United States, he said, and bled in a war as part of that allegiance. He would be a president, “whose fulfillment of his presidential oath is not limited or conditioned by any religious oath, ritual or obligation.”

He went so far in distancing himself from his faith that, while he won popular Catholic support, Catholic leaders were incredulous. A Jesuit publication at the time lamented, “We were somewhat taken aback…by the unvarnished statement that ‘whatever one’s religion in his private life…nothing takes precedence over his oath…’ Mr. Kennedy doesn’t really believe that. No religious man, be he Catholic, Protestant or Jew, holds such an opinion.”

Lopez: Mitt Romney’s problem was that he didn’t get into theological specifics about Mormonism?

Mansfield: An unwritten law of politics is this: When crisis hits, get there the “first-est with the most-est.” Said another way, “hang a lantern on your perceived weaknesses.” Said even more threateningly, “air out your secrets or someone else will.”

Mr. Romney, a gifted and accomplished man, knew that his Mormonism was being held against him in the 2012 presidential race. As he is heard to complain during his campaign in a Netflix documentary entitled Mitt, “I’m just the Mormon flip-flopper!”

Yet he resented questions about his faith and in his convention acceptance speech treated the whole topic in just three words: “We were Mormon.” That’s it. Three words. It wasn’t necessary for him to apologize for his religion nor to explain every nuance of its doctrines. It was essential that he explain Mormonism’s influence upon his political thinking and thus his intentions in office. This no more than ought to be asked of any presidential candidate with a defining religion.

Lopez: So a Catholic candidate should be talking transubstantiation on Meet the Press?

Mansfield: No, because transubstantiation has nearly nothing to do with public policy. Yet that Catholic candidate should be willing to discuss encyclicals on capital punishment, papal proclamations about social justice, the Catholic teaching on the family, and whether bishops should forbid the Eucharist to pro-abortion candidates. All of this and more is appropriate, the legitimate topics well-meaning voters and journalists should be willing to probe.

By the way, such questions are all the more pressing given our post-modern “faith buffet.” More than people join faiths today, they curate portions of disparate religions into customized faiths of their own. If a man claims to be a Roman Catholic, is he a Joe Biden Catholic, a Marco Rubio Catholic, or, as one women recently announced to me, “a Buddhist Catholic.” The word alone does not tell us what we need to know. Neither does Methodist, None, Presbyterian or, for that matter, Muslim or Hindu. The only way to penetrate this veil of customization is to “ask the question.”

Lopez: You describe Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln as “nones” — believing in God but not belonging to a church. Does the comparison to today’s nones stop there, though?

Mansfield: No. Both Jefferson and Lincoln also doctored traditional doctrines to suit themselves, were offended by much of the “organized religion” of their day, and underwent such winding spiritual “journeys” that it is difficult to assess the whole of their religious lives. Only individual seasons of faith emerge with clarity. Today’s nones would find none of this strange.

Lopez: Your life was threatened in response to your writing about Barack Obama’s faith? What on earth was that about?

Mansfield: It was a very strange episode in my life. I was known mainly for writing a bestselling book on George W. Bush’s faith when I wrote The Faith of Barack Obama. Though I do not agree with Mr. Obama’s version of Christianity or the politics it produces, I treated his faith as a genuine feature of his life in my book, rather than assuming he was either a closet atheist or a Muslim pretending to be a Christian for political gain.

This infuriated some people who thought I had become an apologist for an “evil man.” As a result, a fairly vicious campaign arose against me online. At first, I regarded it as an overflow of the intense hatred some Americans feel for Obama. Then, several people stepped over the line and threatened my life. They did so in such specific ways—meaning that they showed knowledge of my personal life—that I had to take the threats seriously. I turned the matter over to authorities. I can’t say much more than that for obvious reasons. I can say it was ironic to find myself in danger for stating facts about a man with whom I almost completely disagreed.

Lopez: You dedicate your book to John Seigenthaler Sr. How did he inspire you? What did he teach you about faith and public politics?

Mansfield: I began my writing career in Nashville and John Seigenthaler loomed large there at that time. He had been a Kennedy administration official, was brutally beaten when he rode with the Freedom Riders, helped start USA Today, and was the leading light of Vanderbilt University’s First Amendment Center. He was also present when Kennedy gave his famous speech on religion in Houston.

I first met him when I was a guest on his public television talk show called “A Word on Words.” He “took a liking to me,” as they say in the South, and strongly encouraged me to continue exploring and writing about the influence of religion in American politics. It was an emphasis in his own work and of the First Amendment Center. To have such an eminent figure tell me I was on the right track and that my writing had value meant the world to me, as it would have to any author. Our relationship grew from there. He truly was a friend and an inspiration.

Kathryn Jean Lopez is a senior fellow at the National Review Institute and editor-at-large of the National Review Online. She is co-author of the newly updated edition of “How to Defend the Faith without Raising Your Voice” (available from Our Sunday Visitor and Amazon.com).