In the immortal words of that great philosopher Woody Allen, “I’m not afraid of dying … I just don’t want to be there when it happens.”

Coming in a close second to death is suffering. Nobody really cares for it much. Even Jesus’ human nature recoiled at the prospect of what was waiting for him at Golgotha and pleaded to be released from the obligation.

But then he got a grip on himself and accepted God’s will.

The Governor of the State of California — someone who was afforded an elite Catholic education — inked his name at the bottom of a bill that now makes it legal for doctors to end the suffering of terminal patients on their own terms. In other words, according to their will, not … you know who’s.

Suffering, as is death itself, is the result of the original sin of our first parents. And suffering excommunicated from that context and from the redeeming essence of the cross and resurrection, certainly can seem pointless.

Either way, it hurts. I have watched my father and brother suffer with terminal cancer and I am absolutely certain there is no one reading this who doesn’t have their own firsthand account of either personal suffering or watching someone they love experience physical, emotional or spiritual pain.

And if it wasn’t for the cross, and more importantly, the resurrection, then I would probably be signing up for a prescription of pills when my time to suffer comes. But that is not what the Church in her wisdom teaches, and that is not what the culture, even the pop culture of television and movies, used to support.

We call them tearjerkers — the movies and television shows that deal with oh-so-sad themes like suffering, usually attached to a premature death or some vile disease. My sons and I poke fun at their mother when she is watching one of these movies and the requisite sad scene comes on and she begins to cry on cue.

Suffering can induce empathy and that is a not a bad thing. Movies that fall into the tearjerker category were all about suffering, but at least suffering with a purpose.

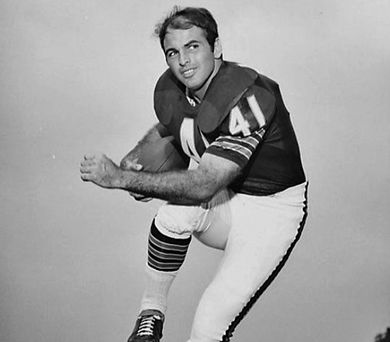

One of the biggest television movies of all time is “Brian’s Song,” a true story about a Chicago Bears running back who was friends with Hall of Fame halfback Gayle Sayers. Brian Piccolo, a journeyman player, became famous when his story about contracting cancer and dying from it became public knowledge.

His struggles and suffering impacted the people in his life and based on the huge ratings, a broad swath of the television viewing public. I will neither confirm or deny whether I shed a tear, but the classic format of this true story and how suffering, as unpleasant as it is, can be transformed into something higher was achieved to great effect.

Even though television shows and movies of the past tended to sanitize suffering — I doubt if the death of the real Brian Piccolo was as peaceful and pain free as it was shown — the essence that it was a path to something better remained constant.

Not so much these days.

Clint Eastwood, a Hollywood icon if there ever was one, is all over the map when it comes to portraying suffering. In his film “Million Dollar Baby,” he “mercy” kills the female boxer out of love because she is in a state of suffering.

The stake this movie claims is that it was better to die than to suffer. Yet in his film “Grand Torino,” his character — who has suffered the loss of his wife, the loss of the life he knew and is in the beginning stages of cancer — struggles courageously onward, changes the lives of the people around him for the better and even dies a sacrificial death, complete with crucified pose.

Maybe these kinds of movies and television shows will disappear from the landscape altogether in our brave new world of prescribed death. Audiences will watch dwindling examples of this kind of drama, thinking to themselves, “Why doesn’t the character who is about to suffer run to a doctor and get some pills and put themselves out of their misery?” We used to say that about our pets when they had reached the end stage of their lives. And with the new law in California, there now seems to be less daylight between us and a toothless Rottweiler.

Thank goodness for Netflix. There you will find plenty of tearjerkers that not only tell compelling stories, but will make you think and not cause you to check your Catholic moral ethics at the door.

One of my favorites is “Titanic.” Not the James Cameron multi-gazillion dollar blockbuster, but the 1953 version with Clifton Webb and Barbara Stanwyck.

It is a rather adult themed film about an estranged married couple with a lot of self-inflicted suffering. When the iceberg hits the propellers — spoiler alert: the boat sinks — Clifton Webb’s character is faced with a decision to make about his own suffering.

I guess he could have just taken a swan dive off the Lido deck and ended it all, but he does not. I won’t spoil this element of the ending for you, but in our current age when “mercy” now includes death by physician, it’s a little comforting to spend an hour and half with a movie from the past and see how things once were, and should be.