Anna Lidzbarski’s parents were from what was then Eastern Poland and is now the Ukraine. They were Catholic.

rnrn

“In that part of the world, Ukranians and Poles and Jews all lived together. My father’s best friend, from the time they were toddlers, was Jewish.”

rnrn

Anna’s parents had been married in February 1938, the year before the war broke out. They were staying with their closest neighbors, Ukranian friends, preparing for a house-raising.

rnrn

“My father was a radio operator in the Army reserves. That night the local constable came with a telegram telling him to report the next day,” she said.

rnrn

“War is very dull, very slow. It’s not like in the movies where everything happens at once. It’s like the frog you put in cold water and start heating the pot, little by little by little. You learn to accept each tiny change. You don’t even realize what’s happening.”

rnrn

All over the country, people had spread rumors, trying to pit one group against the other. Because of nocturnal home invasions and other terrorist attacks, no one knew who to trust anymore. People were afraid to talk to each other. The Ukrainian family Anna’s parents had stayed with were eventually murdered by Ukrainian terrorists, an example of what happened to those who associated with Poles.

rnrn

In 1942, when the Germans came in, at first everyone gave a sigh of relief. They hoped some order would make them feel safer. They started telling people, “Come with us or stay and take your chances with the terrorists. You can come to work in Germany.”

rnrn

“That was the way it was put: a psychological lie in order to control the people. They took the Jews out first, then the Poles. People who didn’t want to leave were forcefully collected. The leaders were taken out first, then little by little, everyone else, too.”

rnrn

In September 1942, the Germans were pulling out. “You’d better come with us,” they said. People had an hour to report to the train. Anna’s parents had two small children by then. Her mother was just pregnant with her. Her mother’s youngest sister happened to be with them at the time, and Anna’s father claimed her as a child from his first marriage, so the family could stay together.

rnrn

They went directly to Dachau. The trip isn’t long distance-wise, but they were four weeks in a boxcar. There was no sanitation, just a hole in the ground. People were emaciated and broken by the time they got to the camp.

rnrn

“If you didn’t end up with a job or assignment after three months, you weren’t going to survive. You could see what was happening to people around you.”

rnrn

Every day the men would have to stand hours in the cold for roll call. If a man fainted during that time, he was taken away and never seen again. After three months Anna’s father was so weak that he was down on one knee one morning, praying for the strength not to fall over. Suddenly someone above him said, in German, “Do you have a family?”

rnrn

It was November 1943. They were all put on a truck and brought to a Dachau subcamp in Rosenheim.

rnrn

An annex next to the krankenhaus [hospital] was used for medical experiments on children. “Helena, my father’s firstborn, got pneumonia and died there. She was given drugs and turned blue in an anaphylactic shock reaction. She was 5 years old.”

rnrn

The Nazis had recently suspended their practice of drowning or otherwise exterminating newborn babies. After Anna was born, the story goes, the doctor put her under a cold tap water faucet, laid her on a table, and gave directions that she wasn’t to be touched or wrapped for 24 hours. Another little baby boy was born the same morning. As soon as the doctor left, a kind nurse named Anna wrapped the two babies up and took them to their mothers.

rnrn

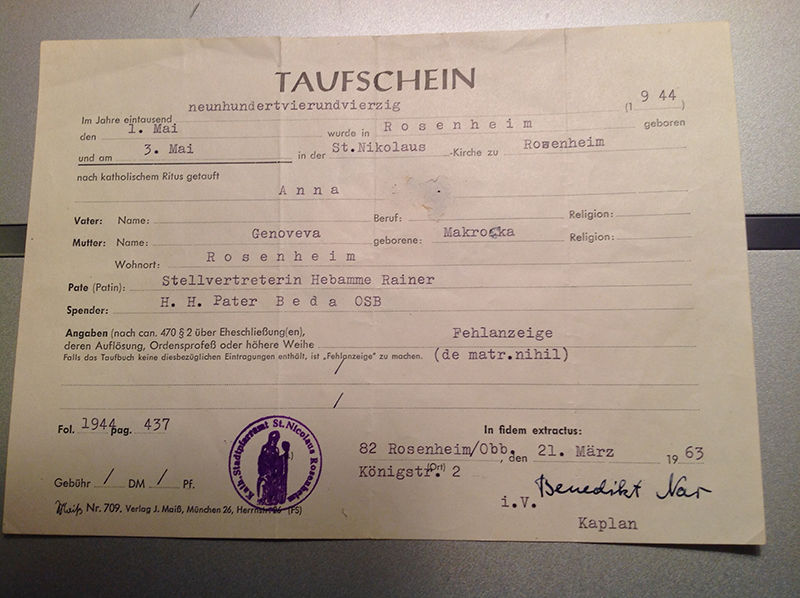

“My mother knew the chances of my dying in the camp were very high. She was terrified that I would die without having been baptized. Anna put me and the little boy in one pillowcase, brought us to the local church to be baptized, and brought us back. She named me Anna, after herself.”

rnrn

Dachau was liberated in May of 1945. The family moved to a series of refugee camps and, sponsored by the National Catholic Welfare Conference, eventually made their way to San Antonio.

rnrn

“On faith, my parents never doubted that I’d been baptized. It wasn’t till 1963 and I was about to get married that Father Peter Colton, my parish priest, wasn’t so sure about the story. He asked a friend of his from the seminary, Father¬†Wesoly, to go to Rosenheim and check the records of the local church. And there the story was verified.”

rnrn

Twice widowed, Anna nursed her mother through her final years. She has four daughters and is a great-grandmother.

rnrn

There was one detail about their time in the camps her parents never forgot.

rnrn

“Bavaria was very Catholic. As they were herded to their daily work assignment, they’d see how the German people were walking and praying the rosary. That Christian witness let them know they were not alone. There was hope in the world. There were people praying.”

rnrnrnrn

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books.

rn